By Daniel Garrett

By Daniel Garrett

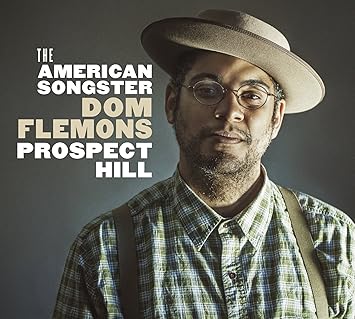

Dom Flemons, Prospect Hill, Music Maker Relief Foundation, 2014

Dom Flemons, What Got Over, Music Maker Relief Foundation, 2015

Smithsonian Folkways, The Classical African American Songsters, 2014

Keb Mo, BluesAmericana, Kind of Blue Music, 2014

I.

Dom Flemons, Prospect Hill and What Got Over

Folk culture is the culture of ordinary people, often in difficult circumstances. It is culture for everyday use—the way work is done and knowledge is shared and meals are cooked and music is made. The songs emerge from work and play, often in commemoration of fundamental events and relationships—birth, childhood, friendship, rivalry, romance, school, marriage, illness, and death. The songs of Dom Flemons and Keb Mo and of earlier and older classic African-American musicians are part of a black string-band tradition that goes back many years, influenced by Africa—the banjo is an African instrument (the word banjo may be related to the Kimbundu word mbanza, although various cultures, of the Igbo, and Mali, Senegal, and Senegambia, had similar instruments with a gourd, neck, and strings)—but it is a music tradition unique to life in America, with all its difficulties and possibilities. Traditions—popular and modern—are often built on the foundations of folk culture; and traditions give birth to artists and intellectuals who then explicate the roots of a necessary culture, a culture that soothed pain and brought pleasure in hard lives in which people were determined to survive, a culture that has begun to be neglected or forgotten. Dom Flemons and Keb Mo remember—and restore.

The Arizona guitarist and harmonica player and English literature student Dom Flemons—with Rhiannon Giddens and Justin Robinson, a member of the African-American string band the Carolina Chocolate Drops—is a researcher and celebrant of the American folk song tradition, knowing its rhythms and its stories, and most of all, its sources, and he has brought those songs to different parts of the country and world. Dom Flemons has mastered the idiosyncratic instruments of the field—bones, fife, and quills and snare drum. Someone who has regard for Howlin’ Wolf and Phil Ochs, Hank Williams and Chuck Berry is someone who can help to heal the breach between regions and cultures—but first conflicts and distances must be recognized.

Incompatibility of style and temperament seems the problem in the song “‘Til the Seas Run Dry,” a song with grit and humor, in which the narrator is forced to forget the person he has loved, or tried to love, someone who was contemptuous and cruel: “I’m never gonna take you back / not ‘til the clocks run backwards,” Dom Flemons sings in that song, supported by banjo and clavinet, on the album The American Songster Dom Flemons: Prospect Hill (2014), a beautifully produced package of music, lyrics, notes, and photographs. Warmth and simple pleasures are enough, at least at first, in “Polly Put the Kettle On,” featuring harmonious singing and strong rhythm (guitarist and singer Guy Davis and fiddler Ben Hunter join Flemons), but the narration reveals that suspicions of disloyalty grow there too. The ordinary trials and tribulations of life are the common subjects of folk songs—love and work and taxes and illness and death, experiences that can be relieved, for a little while, by liquor and lust, and some small but genuine sympathy. Sexual insinuation recurs in the folksy “But They Got It Fixed Right On,” an earthy, intense, and amusing piece. Dom Flemons finds the pain and pleasure in many old songs, the string band music of many years past: and Prospect Hill, produced with the Music Maker Relief Foundation, encompasses many tributaries of folk and early popular music, including spirituals and Piedmont blues and ragtime.

The musical historian Dom Flemons explores different eras and sounds on his album Prospect Hill, which received appreciative comments. “Prospect Hill is a well-traveled album, with songs set in locales ranging from Arizona to Georgia, from San Francisco to Nashville,” noted Brian Mansfield of USA Today (July 15, 2014). Dom Flemons told Mansfield that Flemons and his Carolina Chocolate Drop colleagues had found and sung all the music, a vast amount of music, that they had wanted to do together—and that Flemons thought of Prospect Hill as a bridge between the past and the future. Dom Flemons and Prospect Hill have received commendations from The Boston Globe, The Guardian, The New York Times, Paste, and Rolling Stone, among other publications.

A man who has been away from home wonders if he has been gone too long, if he will be expected and welcomed, in the driving song “Have I Stayed Too Long?”—the song’s thumping beat is nearly gospel. In the Prospect Hill liner notes Flemons says that he heard the song on an album by Blind James Campbell and His Nashville String Band, a black string band group. The song is from the perspective of a traveling man who has found distractions on the road but knows his lover at home has found distractions too. The traveler knows disappointment and frustration despite his adventures and pleasures, and wonders if comfort is still to be found in what had been home. It is a familiar question, too (sadly) familiar.

“Georgia Drumbeat” has Ben Hunter on bass drum and Guy Davis on harmonica and snare drum and Brian Horton on soprano saxophone; and it possesses a sultry, southern rural blues feel, and one hears it and imagines bright skies, open fields, little white houses, and train tracks. A seductive woman who makes chaos in a man’s world is the subject of “I Can’t Do It Anymore” and “Sonoran Church Too-Step” is an instrumental, featuring guitarist Guy Davis and fiddler Ben Hunter. “I Can’t Do It Anymore” is given a throaty, uptempo performance, with a jauntiness akin to rock music, and “Sonoran Church Two-Step” has a charming but dense rhythm that sounds a little African and a little Irish to me. “This is a cheerfully varied set, on which he switches between guitar, harmonica, banjo and percussion, with help from equally classy musicians including multi-instrumentalist Guy Davis,” wrote Robin Denselow of Dom Flemons and his album Prospect Hill in the British newspaper The Guardian (February 26, 2015).

Loneliness—with “four white walls and a worried mind”—is the subject of “Too Long (I’ve Been Gone),” a melancholy yet delicate piece, featuring singing both careful and expressive. Guy Davis on harmonica is in duet with Flemons on bones in “Marching Up to Prospect Hill,” an improvised piece, inspired according to Flemons’ notes by the “country harmonica style of Sonny Terry.” It is the most natural marching music imaginable. Sexual experience—the same old male/female trouble, enthusiastic, lusty, leading to conflicts—is the humorous subject of “It’s a Good Thing,” which names a bunch of women, and the drinking and trouble with police that pursuing them brought—a tyranny of transgressions, civil and sexual. No one is constant or true—but one lover soothes the pain inflicted by another. “Grotto Beat” is a celebration of rhythm, with chanting (including comments on backward marching). “Hot Chicken” has references to roosters and chickens and a rabbit and gila monster, all of which seem part of a playful barnyard metaphor for more erotic escapades; and the song has a lazy country beat but blasting horn, and joking attitude; but then some of the lyrics break into very direct comment on the mundane adulteries of country life: “Young man knocked on the window glass / Old man give him the eye / He said, ‘Boy you done had your fun with my wife / Now quit knockin’ on my blinds.’”

Dom Flemons wrote “San Francisco Baby” about a woman he met, and in it he is haunted by her memory; and his singing of it is both crooning and scatting. Dreams of comfort, easy, and wealth seems to possess the man discussed in the closing song “My Money Never Runs Out,” another subject treated with humor. What would it mean for an album to begin with and develop this theme of class difference rather than end with it? (What it be a blues album? Or a political protest album? Or both?)

“The 14 selections total 38½ minutes, and quite frankly as rich and varied as it is, I am satisfied it’s as compact a program as it is. A much longer program might have been too much to comfortably digest,” Michael Tearson wrote of Prospect Hill in the magazine Sing Out!(December 2, 2014). It is no surprise that Dom Flemons has given us already a sequel to Prospect Hill in What Got Over, a short collection, featuring some songs that were recorded but not chosen for Prospect Hill, such as “Big Head Joe’s March” and “Milwaukee Blues” and “Clock on the Wall” and “Keep on Truckin’” and Going Backwards Up the Mountain” and “What Got Over.” Stephen Deusner at The Bluegrass Situation (April 14, 2015) named the extended play recording What Got Over as one of “23 Essential Record Store Day 2015 Releases” for the April 18the commemoration of an annual event of independent music retailers that is intended to bring attention to valuable musical culture and conscious community. On the internet log My Joog, Todd Godbout said, “These songs are too good to leave in the vault. First-timers would never guess these are contemporary songs; full of old time instruments and throwback vocals” (May 21, 2015).

II.

The Classical African American Songsters, featuring Brownie McGhee, Lead Belly, Mississippi John Hurt, and Big Bill Broonzy

The easy confidence of the performers is impressive and persuasive. The simple narratives have a natural drama yet consist of quotidian details. High quality productions—as pristine as one might hope for such old recordings—on The Classical African American Songsters collection, celebratory and restorative, includes the musical work of traveling musicians who performed folk and popular music: Brownie McGhee and Lead Belly and Mississippi John Hurt and Big Bill Broonzy, and Warner Williams with Jay Summerour, and Pink Anderson, John Jackson, Little Brother Montgomery, Bill Williams, Reverend Gary Davis, John Cephas and Phil Wiggins, Peg Leg Sam, Marvin Foddrell, Snooks Eaglin, and Martin, Bogan, and Armstrong. “Nobody catch you stealing, nobody’ll ever know” is a line from “Chicken, You Can’t Roost Too High for Me,” a song that suggests some of the alternatives—beg, borrow, steal, sharecrop, or sing—that many black men faced in years past. The freedom of black men was circumscribed by laws forbidding access to education, employment, and housing; a freedom expressed in sensuality and spirituality, in imagination and art and sports—and pursued with political petitions and protests. The song “Chicken, You Can’t Roost Too High for Me,” performed by Bill Williams, states that you can get more punishment for stealing a chicken than for stabbing a man.

Smithsonian Folkways producer Jeff Place, who worked with music scholar Barry Lee on the archival music project The Classical African American Songsters, defined a songster for Abby Parks of the web site Folk Renaissance (June 24, 2014): “These musicians, if they really wanted to make money and get hired for parties and such, had to know the hits. That’s what the public wants to hear. So these guys would do their blues but they would also have repertoires of all the pop standards that they could play, and they probably got paid more money for playing that.” The songsters shared cultures, forms of experience and knowledge, especially when they traveled from one place to another.

Legends are assembled on The Classical African American Songsters. I must have heard Lead Belly at some point before—but here his clear delivery comes as a surprise and his sound does not seem particularly southern, or regional, when doing “My Hula Love.” The collection allows one to be introduced anew to many performers. And there is something interesting in hearing the phrases from obscure songs that have been quoted—sometimes without attribution—by subsequent (and more famous) performers. Something else: there is an irreducible dignity emanating from most of these musicians. What is the source of it? Self-acceptance? Acceptance of fundamental human experience?

Peg Leg Sam’s “Froggy Went a Courting” is grave and sexy and funny, as the performer carries then moves away from the melody line with asides and interjections, ending with a spoken signature (self-identification). “The Boys of Your Uncle Sam” by Pink Anderson has topical political references, mentioning the Kaiser and changes in the European scene. “Honeysuckle Rose” as performed live by Warner Williams with Jay Summerour is one of the best versions ever of the song—achieved with only voices and guitar. The album The Classical African American Songsters has been highly recommended by Blues Matters magazine (August 24, 2015), and it is available through the Alternative Distribution Alliance, and respectable and well-stocked brick-and-mortar and online music stores. Certainly, I recommend it.

III.

Keb Mo (Kevin Moore), BluesAmericana

Kevin Moore, better known as Keb Mo, an inheritor of the tradition established by classic African-African songsters, has his own take on the blues—presented with careful craft, intelligence, and practicality—on his album BluesAmericana, produced by the musician with Casey Wasner. There are recognizable elements—hard times and deep grooves—but they do not seem lazy or presumptuous. In “Somebody Hurt You,” one can hear the blues as well as gospel in the slow, downbeat pace, and its lyrics are full of compassion. “You roll the biscuits. I’ll make the dough,” Keb Mo sings in “I’m Gonna Be Your Man,” a composition of commitment, a fulfillment of traditional expectations. Acknowledging difficulties, infidelity, the limits of leisure, and the need for change, “Move” has warmth and a modern, moderately fast tempo. A woman’s efforts have reformed a man’s behavior but he, the narrator, says, “I like the old me better” (in the song of the same name, for which Keb Mo is supported by the California Feetwarmers). International relations, current events, and personal inclinations are the themes in “More For Your Money,” an amusing take on the common, public life. BluesAmericana is a concise collection.

“After all the years of going between genres, I thought Americana seems to be very encompassing, and blues is a part of my experience,” Keb Mo told Brian Mansfield of the newspaper USA Today (April 15, 2014), when discussing his album BluesAmericana, which is elemental in more than one way: an exploration of folk music, and an expression of personal experience, a work of feeling and order, taking on love, disappointment, doubt, lust, jealousy, and sympathy. The musician has said that the album was inspired by the challenges of married life. Keb Mo’s discography includes his first self-titled album in 1994 and Just Like You (1996), Slow Down (1998), The Door (2000), Big Wide Grin (2001), Keep It Simple (2004), Peace Back by Popular Demand (2004), Suitcase (2006), Live and Mo (2009), The Reflection (2011), and The Spirit of the Holiday (2011). “Despite the singer/guitarist’s early affiliation with Robert Johnson, his albums have been more informed by an easy on the ears pop/blues/soul mix that hewed too close to snoozy to have much bite,” wrote Hal Horowitz of American Songwriter (April 22, 2014) of Keb Mo’s oeuvre, while considering the new music, BluesAmericana; however, Horowitz found Keb Mo’s BluesAmericana more impressive and satisfying, concluding, “It’s clear that Mo’ put his heart into these tunes and even if they’re not as rootsy as the album’s title suggests, this is a warm, relaxed and enjoyable set that creates an effortless and natural blues/soul groove.”

On Keb Mo’s BluesAmericana, in the song “The Worst Is Yet to Come,” the narrator misses breakfast and lunch and gets a two-week notice that he is losing his factory job and yet he attempts affirmation. The song has clarity, feeling, rhythm, and texture—despite the doomful foreboding, the music suggests that the Keb Mo narrator has the energy and wit to survive. The singer advises that although somebody hurt you, “all you got to do is just let it go” in the song “Somebody Hurt You,” a blues song with gospel hidden within, offering solace for suffering; and the narrator thinks that after doubt and disappointment he has found finally love’s perfection in “Do It Right,” inspiring him to be a better man, to give more of himself—and in that midtempo song of purpose and resolve one hears different elements—male barbershop singing, folk and country music, and rock. “You roll the biscuits, I’ll make the dough,” Keb Mo sings in “I’m Gonna Be Your Man,” promising to take things easy, to go with the flow, to rise to the occasion.

Yet the narrator—sounding firm and fit—in “Move” is broke when the landlord comes, begging for more time in a world of betrayals and shallow indulgences. The sure voice and strong rhythm convey a strength despite the described circumstances. Duty and its demands, and recognizing one’s own faults are the subject of “For Better or Worse,” mostly voice and strings, featuring a spoken recommitment, simple and contemplative and still dramatic. Marriage and its hardship are the focus of more than one song. Does one accept or try to change human nature; and what does either mean? “He broke down my bed, and loved my woman, on my floor,” sings the narrator over a heavy solitary beat and slow rhythm in “That’s Alright,” which seems a strange acceptance of infidelity. An acceptance of self occurs in the funny “The Old Me Better.” The album closes with “More for Your Money” and “So Long Goodbye.” The amusing song “The Old Me Better” is well-composed; and “More for Your Money” contrasts contemporary references with an old-fashioned musical setting; and “So Long Goodbye” is somber and pretty—with what sounds like nice brush work on the drums.

Purchasing link: http://www.cdbaby.com/cd/domflemons1

Daniel Garrett has written about art, books, business, film, and politics, and his work has appeared in The African, American Book Review, Art & Antiques, The Audubon Activist, Cinetext, Film International, Offscreen, Rain Taxi, The Review of Contemporary Fiction, andWorld Literature Today, as well as The Compulsive Reader. Author contact: dgarrett31@hotmail.com or d.garrett.writer@gmail.com