Reviewed by Ruth Latta

Reviewed by Ruth Latta

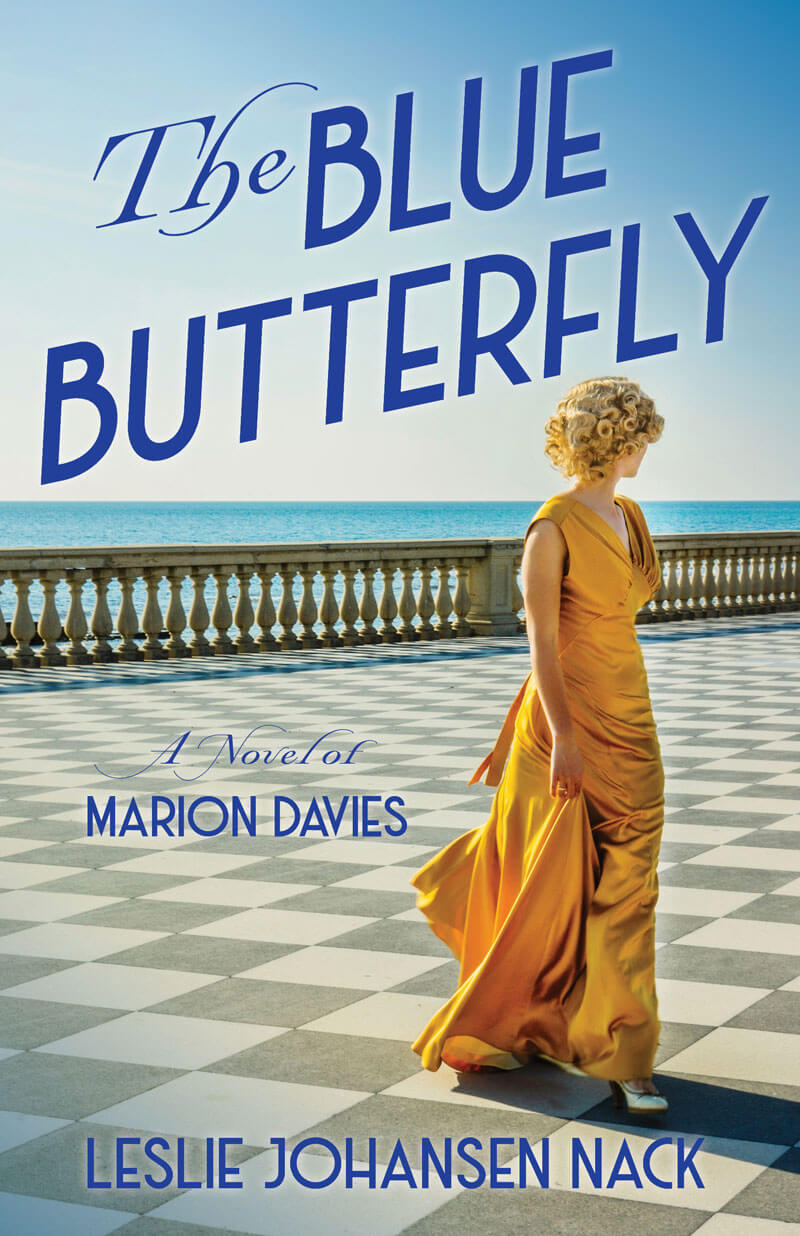

The Blue Butterfly

A Novel of Marion Davies

by Leslie Johansen Nack

She Writes Press

Paperback, 352 pages, ISBN-13: 978-1647423476, May 2022

Was Marion Davies a victim? A woman who paid dearly for what she received? A girl who just wanted to have fun? Is her life a cautionary tale or a success story? The urge to find answers to these questions will keep readers turning the pages of The Blue Butterfly by Leslie Johansen Nack.

Ms. Nack portrays Marion Davies (1897-1961), the long-time mistress of newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst, as a talented woman with loyalty, fortitude and a strong work-ethic. Her depiction of Marion does much to dispel the impression of her created by Orson Welles in his movie Citizen Kane, which centred on a thinly-disguised Hearst, called “Kane” in the film. The movie characterized Marion Davies as a “drunk, talent-less, bored, spoiled has-been.”

At age nineteen, Marion met fifty-three year old Hearst, the richest man in America. He was also married to a former showgirl, Millicent, and was the father of five sons.

“Mother had four girls to raise in a society that favoured wealthy men,” Marion says in the novel. The theatre seemed to be as a place where they might find rich husbands, so she moved her daughters from Brooklyn, where her husband was a judge, to “the semi-posh neighbourhood of Gramercy Park in Manhattan, to be closer to Broadway. When the older girls changed their name from “Douras” to “Davies”, the rest of the family did too, except for their father. Marion, the youngest, began her career as a dancer at seventeen.

Marion’s story, and William Randolph’s, is well documented in a number of biographies including an autobiography by Marion. Since their lives are already well-known, there was no reason to avoid “spoilers” in this review. This historical novel, Nack’s first, is in the tradition of many entertaining and enlightening works such as Paula McLaine’s The Paris Wife and Love and Ruin, Nancy Horan’s Loving Frank, and Amy Bloom’s White Houses. Novels presenting real people as fictional characters, abiding by the facts through careful research, interpreting the past and suggesting lessons learned are a significant contribution to a reading public that is often badly educated about history.

While dancing in Ziegfeld’s Follies, Marion Davies noticed an older man in the audience smiling at her. He sent her roses every week with notes saying, “You were wonderful!” and “I adore you!” Then he disappeared for a few weeks, a pattern Marion came to know well. When he returned and she met him he said, “Your dancing brings me happiness.” Roses and jewellery kept coming. Her mother thought she shouldn’t accept gifts from a married man, saying “There is no legitimate future there,” but when “W.R.” (Marion’s name for William Randolph) came back to New York he made her an offer she couldn’t refuse – her own apartment. Their affair began. His nickname for her was “Rosebud.”

“At nineteen I had two lives,” Marion says in the novel. W.R. promised to marry her as soon as he could get a divorce, but meanwhile it would cause a scandal if they were seen in public together. He offered her movie stardom, founded Cosmopolitan Pictures to produce her films and lavishly publicized her first movie, Cecilia of the Pink Roses, to the objections of his wife who said he was making a fool of himself promoting “that girl”. At that juncture, W.R. broke the news to Marion that his wife would never agree to something as scandalous as a divorce and risk being a social pariah.

Marion’s life as Hearst’s mistress was a roller-coaster; every blessing was mixed. When he bought homes for her family on prestigious Riverside Drive, she was awed and delighted, but saw that she has “traded [her]self for her family’s well-being.”

Marion threw herself into her work, making four or five movies a year. Ironically, while filming Getting Mary Married she found out that she was pregnant. She wanted to keep the baby; W.R. didn’t. When Marion’s sister Rose Van Cleve suffered a miscarriage, Marion asked Rose, and George Van Cleve to adopt her baby. They agree, and W.R. puts them up in luxury in Paris until the baby is born and given to Rose and George. Marion would have preferred to raise the baby herself in Paris, where people were less judgmental than in America, but this is not an option.

Marion returned to work in 1919. As Prohibition was now the law in the United States, she frequented speak-easies with her friends. She also had an affair. W.R. was often away, tending to his empire, seeing his children and building a castle on his property in San Simeon, California. He also took time out from their affair to seek (unsuccessfully) the nomination for the New York gubernatorial race, with his wife, Millicent, on his arm. When Marion learned that he had spies watching her, she confronted him indignantly, only to hear, “It’s just to keep you safe, my dear.” W.R. cramped her film career by stipulating “no kisses” and “no comedies”. In the novel, Marion admits that she has “everything a girl could ever dream of, except for an authentic life.” She decided to share part of her life with W.R. but not all of it.

Nack’s descriptions of Marion and W.R.’s travels, parties, yacht and many homes, show readers how fabulously wealthy Hearst was. In addition to the penthouse he shared with Marion, his castle at San Simeon and three ranches in Mexico, he had other homes as well. In 1920, when he moved Marion’s upcoming film to Los Angeles, he moved her mother and two of her sisters and bought them a house. Later he build Marion the mansion “Ocean House”.

In Los Angeles, Marion had a ten year affair with Charlie Chaplin simultaneously with her relationship with W.R. Charlie called her his “little blue butterfly”, but had other affairs including one with an underage girl.

In 1924, scandal struck W.R. and Marion on a weekend cruise on W.R.’s yacht. Among the guests were Chaplin and the film producer Thomas Ince, whom W.R. wanted to write and produce movies for Marion. Ince broke his abstention from alcohol and suffered an attack of acute indigestion. He was taken off the yacht, given medical attention and died. Though the coroner’s verdict was “heart failure from acute indigestion” , rumours spread that Hearst, jealous over Chaplin’s affair with Marion, intended to shoot Chaplin but mistakenly shot Ince instead. Author Nack accepts the official version in her novel, but rumours of murder persist into the 21st century; for example, in Peter Bogdanovich’s 2001 movie, The Cat’s Meow.

As Nash shows in the novel, Marion eventually accumulated a considerable independent fortune which she used not only to fund her family members but also to help the Hearst Corporation when it began to crumble in 1937. Dipping into her own assets, Marion contributed two million dollars which tided over the corporation in the short term. It rankled with Marion that Hearst’s wife, who was always supported in style, never offered him financial aid during this crisis, when his empire was failing and put under trusteeship. With World War II, it recovered, though not to its former heights.

After several unsuccessful movies, Marion gave up acting and devoted herself to W.R. until his death at eighty-eight. Millicent eventually got out of their lives and stayed in New York. Although Marion never married W.R., they lived together as wife and husband in California. They never divulged to the world that they were the parents of Patricia Van Cleve, but in Nack’s novel they eventually tell Patricia when she is a young woman, and all three become close.

The Blue Butterfly ends sadly with W.R.’s death and Marion’s exclusion from his funeral. Marion’s relationship with his sons is not explored in the novel, except for a scene where Marion makes friends with two of the sons as teenagers, and later, the information that she is going on holiday with W.R. and all five sons and their wives. It’s a shock to see all five grown men cave in to their mother’s wishes and excluded Marion, especially when she says,“A few of them hated me, a few liked me and one was dear to me.”

In her epilogue, Leslie Johansen Nack quotes Orson Welles’s apology for his negative depiction of Marion in Citizen Kane. He wrote: “She would have been a star if Hearst had never happened.” Did W.R. ruin Marion’s life and career? I would say “No.”. She enjoyed a period of stardom like many actors, though her forty-eight films in twenty years were uneven in quality. She married unhappily and drank too much, but she appears to have been a well-functioning alcoholic noted for her philanthropy, especially to children’s charities. At the time of her death she was the richest woman in Hollywood. The title, The Blue Butterfly, suggests sadness, but my view is that she was a rosebud who became a rose.

About the reviewer: Ruth Latta likes historical novels involving real people. Her latest such novel is A Girl Should Be (Ottawa, Baico, 2021, info@baico.ca)