Reviewed by Charles Rammelkamp

Reviewed by Charles Rammelkamp

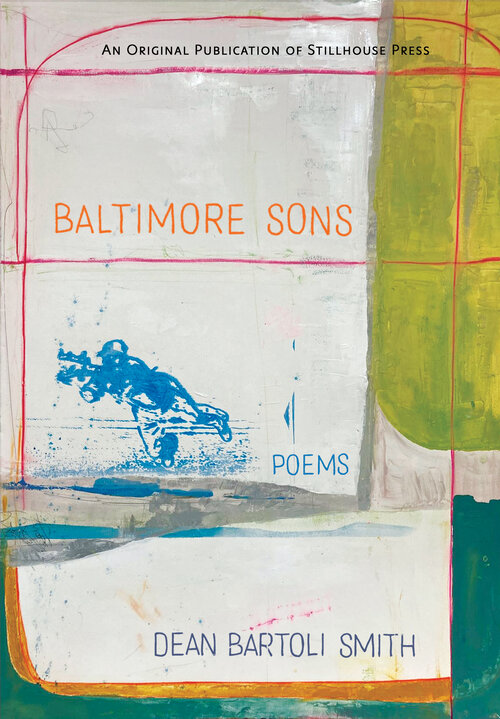

Baltimore Sons

by Dean Bartoli Smith

Stillhouse Press

Nov 2021, $17, 128 pages, ISBN: 978-1-945233-12-8

A profound nostalgia, both personal and cultural, saturates Dean Bartoli Smith’s spare, elegiac poems, which deal generally with America’s fascination with guns. In a poem called “Empty the Chamber,” which takes place at a shooting range, he writes:

My father shows me paper targets riddled

with holes—obliterated faces and hearts.

He grew up in Baltimore; he will make

someone pay for its ruin.

For Baltimore has faded from its glory days, whenever those were. Some might say it was the nineteenth century, when Francis Scott Key and Edgar Allan Poe roamed the streets and major political parties held their nominating conventions in Baltimore. Smith’s nostalgia is for the sports heyday of the 1960’s when Unitas and the Colts ruled football and the Orioles were always in contention, and the NBA Bullets hadn’t yet left town for Washington. In any case, as he writes in “Trash Night, Guilford”: “the city’s gone to the dogs.” The poem “Pistol Range” continues the theme:

Today, he takes the law

into his own hands.

Not a policeman or a soldier,but a disgruntled son

out for revenge. He utters

a list of citations against a fatherwho guzzled money saved

for Christmas presents,

who cheated on his motheras she lay dying of lung cancer.

He kills him over and over,

enjoying every moment.

In truth, Baltimore’s population peaked at 939,000 in the 1960 census and has since dropped by 300,000, partly because of “white flight” after the 1968 riots. In his poem “Baltimore,” Smith writes:

Pop-pop bragged

about the sawn-off shotgun

he kept in his lap

while driving a potato chip truck

in case anyone got funny with him

during the riots of ’68.

The title poem, “Baltimore Sons,” begins:

Three-hundred and forty-three

people murdered last year

in Baltimore,mostly with handguns,

the weapon of choice,

obtained illegally,almost all victims and suspects

previously arrested,

mostly gang membersin drug crews using

guns on rival

gang members,muscling in on

or defending turf

or retaliating for past acts,

The situation is recognizable to anybody who has watched David Simon’s HBO series, The Wire (to which Smith alludes in the poem, “Riots”). The poem “McKenzie” is about the three-year-old victim of a drive-by shooting. But America’s fascination with guns goes way beyond this. In poems like “Six Shooter” and “Outlaw” and “Ordnance” and “Cap Guns,” Smith writes about the casual way in which guns and retribution fantasies play a part in childhood. In “Cap Guns” he writes:

We played Gunsmoke,

took turns as Festusand Marshall Dillon twirling

mother-of-pearl Colt .45sdown Northwood Drive,

fast becoming outlawswith bandanas over our mouths,

yelling, “This is a stickup!”Brendan and I, officers

Reed and Malloyfrom Adam-12,

pointing die cast .38sacross the hoods

of imaginary squad carsyelling “Hold it!” and “Come out

with your hands up!”

Smith also writes about a broken childhood, conceived in the backseat of a ‘58 Thunderbird, Irish-American father and Italian-American mother (“Shotgun”: “I was conceived by mistake / in the back seat of a royal blue Thunderbird”). To traffic in stereotypes, Smith combines an Irish sentimentality with shitkicking Italian bravado throughout Baltimore Sons. Indeed, Smith himself wryly writes in “Pure Shooter”:

I’m half-Italian, half-Irish,

coming from hubcap stealers

and horse thieves,

narcissists and nuns,

a natural bipolarism.

In “Cash for Guns, 1975” he writes about his father’s Remington deer rifle, “Before the divorce I’d sneak / into my parents’ closet, unzip / the rawhide sleeve and lift / the rifle out.” The poem ends:

Dad was behind

on his child support.

He needed fifty bucks

for food. I watched him walk

slowly to the police station,

cradling the rifle like a son.

In place of the dysfunctional family, then, the world of sports stars fills the void. In poems like “Unseld” “Sportswriter” and “Memorial Stadium” Smith writes about the local teams and players and how much they meant. The poem “Final Out” is a sweet elegy for the star Orioles pitcher Mike Flanagan, who committed suicide – with a gun – in 2011. In “Memorial Stadium” he writes:

The Orioles eked out victories in bushels,

with all of us part of a makeshift family,

and we loved each other from all over town

in “The World’s Largest Outdoor Insane Asylum,”

huddled together in the bitter December air

to watch the Colts rise on their back hooves

in response to a bestial din boiling over:

a doomed and obsessive love affair

between a city and its heroes

created an unbroken family

of Black and white stars…

It is mainly the first part of the Baltimore Sons that spotlights Baltimore. In Part II Smith widens the lens, while still focusing on guns, violence and injustice. “Gwendolyn and Freddie” takes off from the 2015 police murder of Freddie Gray and the civil unrest that followed but the emphasis is on the racial inequality, just as poems like “Reading James Baldwin on Election Day in Charleston,” “Lieutenant Fox,” “Something to Cool You Off,” “Decoys” and “Eady Does the Eagle Rock,” a poem about the shabby treatment of the poet Cornelius Eady in a Chicago restaurant, likewise do.

The poems, “.357” and “.45” are gun poems from the point-of-view of the gun. The latter ends, “My owner is not

a bad man, just inclined toward freelance

law enforcement, a fan of The Lone Ranger,

and afraid that society as we know it is coming

unhinged, and it makes him feel better

to turn the pistol on the target of his anger.

I’m just afraid that I will be used to shoot

an unarmed stranger, and then be blamed,

which couldn’t be further from the truth.

“Shooting Gallery” is a poem that takes on the gun violence at Sandy Hook and at Virginia Tech and elsewhere, and “Delivery Room” is about the birth of child – Smith’s daughter Julia – during the pointless violence of the Iraq War, kids “from Kansas, Oklahoma and Michigan” killed in “Basra, Najaf, Tikrit.”

In addition to his elegy for Mike Flanagan, Smith writes another, “One Blow to the Brain,” for another gun suicide, the young writer Breece D’J Pancake.

But Smith saves his most moving elegies for his mother. “The Viewing” takes place after his mother’s death, but it’s the final three poems that address the grief. “Misericordia Blues” starts:

I played a concert for the ghost of my mother

three days after her death in the room

where she lay dying for five days,

And later in the poem Smith remembers playing songs for her while she lived.

Sometimes I cried while singing the songs

because death was not a word I associated with her.

She loved “Bobby Dylan” so I played “Tangled Up in Blue”and “Forever Young” and Neil Young’s

“Cowgirl in the Sand” and “Ambulance Blues”

for the Italian Health Service, with its paramedicsin sky blue and gold Thunderbird suits, who arrived late

on her last day, only to dump her into the chaos

of an emergency room with the word for mercy—“misericordia”—emblazoned on their truck.

She held my hand and my brother’s and said,

“We sure fucked this one up, didn’t we?”

“Warrior,” which follows, is addressed to his mother, at her deathbed,

with your boys

gathered aroundthe headboard

and you, a long wayfrom Iris Avenue

in East Baltimore

And in the final poem, called “Three Poems of Departure on Route 96,” he reflects on his mother, her life, her passing. The poem and book end on the line: “This is when I knew.”

The melancholy reminiscence at the heart of Baltimore Sons is affecting and admirable. The reader joins in the horrors and sadness with a cathartic response.

About the reviewer: Charles Rammelkamp is Prose Editor for BrickHouse Books in Baltimore and Reviews Editor for The Adirondack Review. His latest book, Catastroika, was published in May 2020. A chapbook of poems, Jack Tar’s Lady Parts, is available from Main Street Rag Publishing. Another poetry chapbook, Me and Sal Paradise, was recently published by FutureCycle Press. An e-chapbook has also recently been published online Time Is on My Side (yes it is). Another chapbook, Mortal Coil, is forthcoming from Clare Songbirds Publishing.