Reviewed by Juliana Convers

Reviewed by Juliana Convers

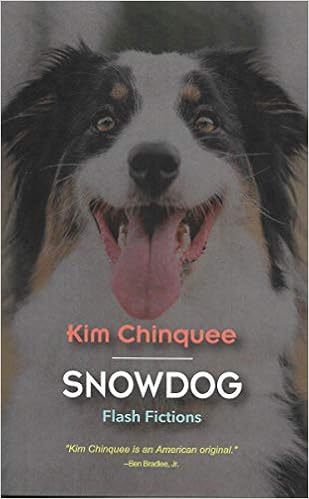

Snowdog

by Kim Chinquee

Ravenna Press

Jan 15, 2021, Paperback, 80 pages, ISBN-13 : 978-17351131

You don’t need to love dogs to love this collection, but it helps. While they are not always the focal point of each piece, the dogs that appear throughout this collection are totems of security, outlets for maternal nurturing, fountains of unconditional love, and harbingers of optimism. They are anchors for memory and time, marking routine with cold noses in the mornings, their separate feeding dynamics based on their unique gobbling habits. In the absence of children, they are something to care for. And like children, they are hypersensitive beings who are too often the collateral damage in home schisms. Their presence serves as a reminder––as perhaps any pet-lover would agree––in the midst of life’s chaos and disappointments, of innocence and the simplicity of joy.

Kim Chinquee has been called the “queen of flash fiction” as early as 2010 with the publication of her collection Pretty. Though this was my first foray into her work, I took to her understated style and tough, flawed protagonists. A “Kim Chinquee” narrates nearly all these fictions, in first and third person, sometimes renamed “Elle,” a proxy she also used in Pretty. The author and her narrator share many life details: she is a mother, a girlfriend, an ex-wife, a dog-lover, and a “ripped” triathlete with a military background. Later pieces in the collection explore her memories of auctioning off a family farm, and hint at the childhood trauma of watching a parent suffer with mental illness.

Set mainly in snowy Wisconsin, the first two sections present a portrait of a woman’s life with her long-distance boyfriend and their combined brood of dogs, punctuated with trips to Hawaii to visit her son and his wife. Chinquee evokes both the chill of uncertainty and the warmth of being among loved ones, often within the same space. From one sentence to another, icy heaviness gives way to abundance, warmth, and humor, evoking a bittersweet sense of time’s passing.

Several of these pieces demonstrate the ways in which intimacy can blend our individual experiences into a shared landscape. In an eight-line piece about feet, and featuring donuts, called “Make It Wiggle,” she recalls how, “in his mullet days,” her boyfriend had struggled with low potassium (20). Then she wonders, “Or maybe: was that me?” This mundane detail and the simple query demonstrates the empathic power of intimacy; when we are close, it is easy to confuse the suffering of a loved one for our own.

Even within less intimate relationships, stories––even names––blur or overlap with one another’s. The girlfriend borrows her boyfriend’s mother’s ski shoes, literally stepping into the older woman’s shoes. She shares a first name with her son’s wife, and through marriage, a last name too. She notes how well her daughter-in-law knows her son, down to how he likes his potatoes; “She cuts potatoes the way he likes. I like her. She has the same first name as me. And now, she has the last name. We are, as far as I know, the only Kim Chinquees” (3). And far from implying an attitude of resentment or bitterness, the tone seems to indicate the ways in which we relieve each other of our burdens––perhaps even the burden of uniqueness.

A few of these pieces might pass by the casual reader once, then force a double-take. In the midst of domestic routine and canine devotion, the author sneaks in her punchy wit and flashes of crackling eroticism. I had one such double-take reading “Our Dog Ran Down the Highway,” which opens with a deceptively simple description of domestic bliss: “He came in from work, carrying firewood. He smelled like the string cheese I put in his lunches” (19). The first sentence indicates strong masculinity. But the next sentence, these details of packing a lunch including string cheese, typically a childhood snack favorite, swerved my thoughts to a mother-child relationship. But the mood reverses yet again with the following line, “He put down the wood and bit my neck” followed by, “He grabbed my boob and felt it.” We shouldn’t be so surprised at this turn, given the line break signaling a shift. In fact within this contrast, we gain a

perspective of this woman’s multi-dimensionality as a doting and desirable partner.

In part two, titled “Doodle,” the fictions build on and complicate the scenarios breached in part one. The character of the boyfriend (which I’ve always thought was an oddly infantilizing term for an adult, non-married partner) is eager to be supportive and protective, offering to teach his girlfriend to fire a gun. But his girlfriend (Elle) is more than capable, given her military background. We see her amusement at his well-meaning attempts to step into a stereotypical masculine role for her benefit. Later, we learn that this boyfriend also has an ex, hinting at an additional undercurrent of complexity in their relationship. In the first story in this section, “Goldendoodle,” Elle comes across an old photograph she’s never noticed before, of her boyfriend with his ex. We realize the complexity of their relationship. And yet, the writing sticks

to the facts:

It’s a nice portrait, Jim looking younger, thin, though older than when Elle had

met him. She’s known him longer than the ex. Elle met Jim in high school. They

were sweethearts. After Jim’s divorce, Elle and Jim reunited. The dog’s a

goldendoodle…(25)

Though she avoids expanding on the subject of this ex, is there perhaps a hint of competition? The rate of revelation in these lines moves along swiftly, yet forces us to pause and unwind the relationships and timeline. And though the sentences resist sentimentality, we nonetheless feel the hum of anxiety as her thoughts turn abruptly to the dog.

Indeed, the concise, confident lines in Snowdog often belie and then underscore a heaviness beneath the blunt honesty and humor. Emotional ties to a family home, the concern for grown offspring, and the devastation of losing loved ones seep into the coziness of routine, and flow underneath the joy-spikes of nature and adventure. The piece called “Foxy” begins with the gut-punch line, “I guess we’re not having any babies, I say to my boyfriend.” His arm is in a sling from an injury, and she has had a recent hysterectomy. About their maladies and degrees of temporary immobility, she declares, “This is not like us. We are active. We are athletes” (17). We feel this bewilderment at the aging process, these constant reminders of the limits of our bodies. It is followed by the infuriating sense of having done everything right, only to fall through the ice.

This is a quietly impressive collection for lovers of the flash form, the traditional short story, and of poetic form. It is for dog-lovers, for mothers and lovers, and those for whom the routines, landscape, and concept of domesticity implies a multitude of contradictions and simultaneous truths. In her poised expressions and riddle-like compositions, we come to know the many dimensions of this Kim Chinquee/Elle character and her relationships. Though life could be said to be built upon the comforting perpetuation of routine, the intrusion of memory and the awareness of mortality invite doubt and demand our vigilance. Best to have a furry companion by your side.