Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

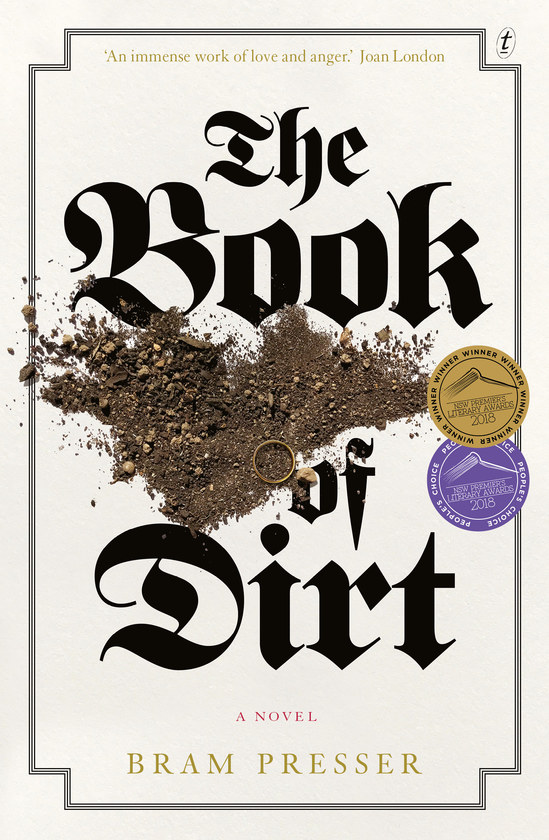

The Book of Dirt

by Bram Presser

Text Publishing

320pp, $32.99au, Aug 2017, ISBN 9781925240269

It’s one of life’s sad ironies that children tend not to want to know their family histories until it’s too late. My grandfather never spoke about his WW2 experiences, and the subject was clearly off-limits to us, though he was active in veteran associations. I’d love to sit with him now and coax it all out, especially the most harrowing parts , but that’s no longer possible. I only have one letter and several photos. Similarly, stories of the pogroms that led to my great-grandparents’ on both sides leaving Eastern Europe in a mass diaspora were not spoken of. This was the past. No one wanted to rehash what was traumatic, but these untold stories remain deeply imprinted in my sense of who I am–it is as much my story as theirs.

Bram Presser’s The Book of Dirt is a novel built around this conundrum. The book recreates the story of his grandparents Jakub Rand and Daša Roubičová, who met in Theresienstadt, Czechoslovakia, a hybrid concentration camp and ghetto used primarily as a transit point for Czech Jews en route to their death at Auschwitz, Majdenek, and Treblinka. Presser’s grandparents and actively avoided the subject of their time in Theresienstadt, so Presser was both shocked and intrigued when he came across a newspaper article about his grandfather’s role as “privileged Jew” in the camp, working the Talmudkommando, a little known group of Jewish scholars, cataloging artefacts for ‘Hitler’s Museum of the Extinct Race.’

Presser manages the most delicate of balancing acts, working between real material including photographs, documents, articles, a cache of letters he found, records like the Theresienstadt Memorial Book and the real names he finds there (“Everyone who has died begs to be remembered”) and the fiction of imagination, story, and rumour, filling in gaps and pulling together a linear tale that is both engagingly readable, and full of the complexities of trauma and uncertainty. The book doesn’t shy from these dichotomies, but rather embraces them, allowing for multiple perspectives while remaining rigorous with the notion of truth and what we have a right to invent. The result is rather extraordinary.

The book pulls no punches. From the very first pages we are told “almost everyone you care about in this book is dead.” There is no softening what happened in the camps, and the great love story that drives the story forward is not enough to undo the great evil out of which it grew, nevertheless, it’s no spoiler to say that Jakub and Daša find one another after the war. So much of what makes the present tense of the novel possible comes down to luck, small acts of kindness, and the often random connections that take place. The book is beautifully written, poetic throughout and very moving. There is a lyrical richness and cadence which creates immediacy:

She no longer knows silence. For almost three years there has only been noise. The hubbub of an overcrowded street. Gasps, whimpers, sobs. The steady hum of electricity pulsing across deadly filiments. Dogs: panting, barking, scratching at wood. T he swish of buckets filled with human waste. Screams, coughs. An orchestra of motors. The crunch of heavy booths. Th screeching needle of the loom. The thud of falling sacks. No birds. Never any birds. (280-81)

The Book of Dirt is a critical record, and it is a fable. The quest for the true story of Jakub and Daša is a failure and a triumph. Memory may be distorted, fractured and fading as survivors become increasingly hard to find, and records and artefacts are lost or destroyed. Nevertheless, there is something that continues to survive in the retelling, and this is transformative. The Book of Dirt is a terrible and gorgeous story full of sorrow, joy, magic realism and mythology, careful scholarship, and a rigorous dedication to honesty, even when it’s impossible to make the story fit together into a coherent narrative:

So we search, we sift, we question, we beg, we scream, we suffer, we smash at doors with our shoulder, until we hold those pieces of evidence in our clenched fists. But even then we are left to wonder: whose stories are they; who owns the experience; to what end can it all be used? (69)