Reviewed by Karen Herceg

Reviewed by Karen Herceg

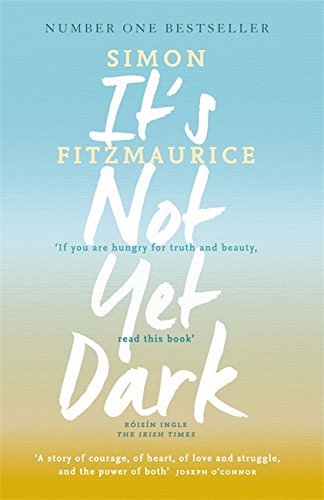

It’s Not Yet Dark

by Simon Fitzmaurice

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing

ISBN-13: 978-1444795189, 165 Pages; $23

One might argue the definition of purgatory or its potential significance, suggesting its transitory station is both punitive and cleansing. The character of its visitor who finds himself in that netherworld determines which qualities best prevail. For Simon Fitzmaurice things were not as bleak as they might have been given the excessively difficult situation he endured. ALS (Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis) or Lou Gehrig’s disease, a progressively devastating neurological condition, ravaged his body and left him completely paralyzed before his recent death on October 26, 2017 at the age of forty-three. ALS affects the nervous system weakening muscles and impacting physical function. As his situation deteriorated, he used an eye-tracking computer and the help of assistants and loved ones to continue his work. A promising, award-winning director who hailed from Ireland, he directed his last film, Emily, in 2015.

Ireland is an alternatingly harsh and lush landscape of rich literary heritage, patriots and ex-patriots at once in communion with it and often validated outside of its controversial confines. Fitzmaurice was a true native son, but his work and messages are universal. In his memoir, It’s Not Quite Dark, he details his youthful aspirations, early successes, the joys of a loving wife and partner and the rewards of a growing, supportive family. The memoir was also made into a documentary of the same name.

These are not so much the pithy, brave proclamations of a man succumbing to bodily debilitation, as they are the steady, courageous acceptance and insightful reflections of a spirit stronger than physical limitations. Simon Fitzmaurice was not to be tethered down but allowed his spirit to take prominence rather than sink, as his corporeal presence took less focus as a vehicle of his worth and value. There is a stark reality and sparseness to his style that is less effusive than more traditional, so-called inspirational accounts typically associated with personal stories of triumph over adversity. In fact it is his terse vocabulary, clarity and focused powers of observation that draw us in, remaining emotionally connected and personal without a lot of treacle or director’s instructions on leading us where we think we should feel. He keeps us anchored in the present, which is where he had to live being so keenly aware of his mortality. But we come to realize that this is the situation for each of us conclusively. Our reminders are not so obvious, which is why we need someone like Fitzmaurice to wave that flag of recognition in front of us. As he tells us, “Everyone notices but no one sees” (P. 1, l. 11).

People are locked into their safe definitions of what it means to be a person, a man, a woman, whether from fear or an inability to accept the fluidity of life itself. Fitzmaurice observes that people looked away from him while children did not because “They are still looking for the definition of a man” (P. 2, ll. 8-9). And this is one of the great gifts of this memoir: it asks us to examine our definitions of life, ourselves and all that is around us in the world, what we value and what is truly valuable. Perhaps the author’s weakening condition necessitated very direct, heartfelt language that forbids wasting words. In recollecting his childhood, courtship of his wife and adventures into fatherhood and career, he expertly dissects how our thought processes and intuitive emotions operate in opposition. When his future wife first hands him her phone number he tells us that he does not call saying, “It’s too important” (P. 7, l. 14). The hesitancy and questioning of his own worth in response to this situation contrasts sharply and ironically with the value he develops for himself after he becomes even more vulnerable during his illness. With this observation, Fitzmaurice was comparing our reticence to act based on a perceived lack of worth to an intuitive knowing that differentiates between distorted personal choice and the innate, natural actions that feel right and compel us to act if we rise to the occasion. He knows how to juxtapose our pedestrian, conditioned thinking as opposed to heeding that inner voice that shows us our true path.

Fitzmaurice wrote with the sensibility of a filmmaker. He blends past recollections, present conditions and future possibilities in a moving kaleidoscope of connectivity regarding one’s influences, hopes and realities that seems always to be present instead of distant and reflective. It promotes an immediacy and intimacy frequently lost in static methods of documenting the past that often foreshadow the future in predictable ways that belie the truth of what we can know and cannot know. There is compelling brevity to his thoughts and assessments, a distinction between self-serving proclamations and presumed bravery as opposed to judgment of others or himself.

The sparseness of Fitzmaurice’s language does not diminish often lovely, succinct imagery such as a description of gateposts that are “lichened and mottled with time” (P. 26, l. 17). Insights come with a sharp, authentic punch, as when he writes, “Adoration has always been a troubling concept for me. Screaming crowds at rock concerts. The suspicion that fame is the will to defer responsibility to another” (P. 32, ll. 8-11). He realizes that identifying with visibility and a high profile cannot save us from ultimate obscurity, save us from fate and ourselves. One could write an entire thesis on these sentences alone.

Fitzmaurice is brutally honest in a plea to feel pain, as if he is somehow responsible for the disease descending upon him, to feel its deep reality for himself and those who love him, “for this loss that we’ve suffered” (P. 37, l. 8). And he did feel the pain in difficult medical procedures and many other instances that mirrored the psychic hurt and intrinsic sense of helplessness. It is a helplessness that we all feel in a variety of ways, and that we deny in an inability to submit to humility and the many fearful implications of a world we truly cannot control. He states, “Our species is defined by asking questions, out into the dark, without anyone to guide us except each other” (P. 43, ll. 18-20). Yet the true connection is the intuitive link to something greater than any of us, greater than the temporal and even one another. He is more on the mark when he observes, “Love. It’s all it’s ever been about. No one’s story is more important than anyone else’s” (P. 69, ll. 20-21), and “To value. To Love. Which is all it’s ever been about” (P. 151, ll. 8-9).

Fitzmaurice refers to “The stark strangeness of this life” (P. 70, l. 4), perhaps because we are temporary visitors here and home is not this place. We live in a world of limitations but also possibilities. Fitzmaurice continued to find fundamental meaning and expression through creativity and his work. However, I would disagree with his statement that having a child is “The ultimate expression of being alive” (P. 102, ll. 9-10). I imagine Fitzmaurice enjoyed much satisfaction and love from his five children, some fathered after his disease had progressed. But it is one expression with multiple implications. As a species we need to love and value ourselves first and, as gratifying as our relationships may or may not be, there are many who know great satisfaction in being alive who have not had children in this lifetime. More to the point, I agree wholeheartedly with his statement that, “Truth does not endure. If it did, a great silence would hang over the earth” (P. 101, ll. 5-6). It’s accurate to say that truth is in a constant battle in this dynamic. We must not cease to fight for it in and outside of ourselves, but it is an ongoing conflict indeed. This is not a paradigm of truth or peace but a place to seek truth and peace. We are given many adversities and advantages on our individual journeys to that place, to heal ourselves in multiple ways. As Fitzmaurice stated, “It’s a beautiful thing to see yourself” (P. 111, ll. 20-21), and that included the thorns and the flaws as well as the fact that “life is a privilege, not a right” (P. 92, ll. 4-5). When we see it from this perspective we no longer become entitled but grateful, not only for those things we perceive as joyous but the challenges that teach us if we wish to grow. Fitzmaurice left us with his greatest legacy when he stated, “There is a certain sickness to always wanting a happy ending, if the desire for it is driven by a fear of seeing things as they are” (P. 160, ll. 8-10).

About the reviewer: Karen Corinne Herceg writes poetry, prose, essays and reviews. Her latest book is Out From Calaboose, by Nirala Publications (2017). She lives in the Hudson Valley, New York.