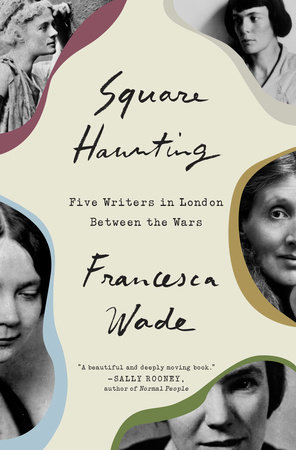

Square Haunting

Five Writers in London Between the Wars

By Francesca Wade

Penguin Random House

Hardcover, rrp$28.99, Apr 07, 2020, ISBN 9780451497796

In 1927, Virginia Woolf published her essay, “Street Haunting”, showing her imagination being stirred on a stroll through London. Author Francesca Wade adapts Woolf’s title for her debut book, because she is writing about five women who came to London to widen their horizons and forge “new narratives for women”.

In Square Haunting: Five Writers in London Between the Wars, Wade profiles the imagist poet, Hilda Doolittle (H.D.); the mystery novelist Dorothy L. Sayers; two scholars/academics, Jane Ellen Harrison and Eileen Powers, and the modernist novelist Virginia Woolf. All five, writes Wade, “pushed the boundaries of scholarship, literary form [and] societal norms in order to have lives of the mind in which their creative work took priority. Several knew each other, several influenced each other, and all five lived at Mecklenburgh Square, though not at the same time.

Mecklenburgh Square in London was full of booksellers and publishers, close to the British Museum, the University of London, the London School of Economics and the West End theatres and restaurants. In the early decades of the 20th century, rooms and flats in this area were within the budget of single working women.

Given that the five women lived in the same area at different times and weren’t part of a group, the Mecklenburgh Square connection is tenuous. The five women are connected in more important ways, though. None of them believed that marriage was woman’s ultimate destiny. Indeed, after so many young men were killed in World War I, marriage became an unattainable goal for many women. Most importantly, all five of Wade’s subjects had a women-centred approach to their work and departed from male models of writing and scholarship. All of them struggled in pursuit of their work.

The classicist Jane Ellen Harrison (1850-1928), a graduate of Newnham College, Cambridge, before that institution granted degrees to women. Despite her academic accomplishments, she, unlike her male counterparts, couldn’t find an academic teaching position for many years. Instead, she supported herself as a travelling lecturer, giving dramatic talks about the classics to working men’s clubs, schools and museums. Finally, at forty-eight, she was awarded a fellowship at Newnham College to lecture and pursue her research.

While male classicists of the period were absorbed in Homer and the Olympian pantheon, Harrison was interested in the recent discoveries about the ancient world by archaeologists like Heinrich Schliemann and Arthur Evans. She travelled to their sites. At Knossos, seeing a clay seal portraying an ancient ritual of mother worship led Jane to delve into the goddess cults which preceded the Olympic pantheon, and to assert that the Olympian gods were a literary and artistic creation, never part of popular religion in Greece. She contended that the myths “originated in an older worship, anchored in emotion and community spirit… which placed the greatest importance on women.” Male scholars attacked her for allegedly over-emphasizing women’s role and for her “florid” writing style.

Jane Harrison published books and learned sixteen languages. In 1922, she and her partner, Hope Mirrlees (her former student, a poet) left Cambridge for good and went to Paris, where Jane found a new area of interest. She learned Russian, associated with Russian exiles, and translated a medieval Russian work into English, which was published by Virginia and Leonard Woolfs’ Hogarth Press. Harrison and Mirrlees lived in Mecklenburgh Square from 1926 until Jane’s death in 1928.

The other scholar in Wade’s book is Eileen Power (1889-1940) who lived in Mecklenburgh Square from 1922 to 1940. Her stockbroker father was imprisoned for fraud, leaving his family financially strapped. At fourteen, she lost her mother to tuberculosis and she and her two sisters lived with some aunts. In 1907 she won a scholarship to Girton College, Cambridge, where she met a number of achieving women, such as Karin Colstelloe, (a future psychoanalyst and sister-in-law of Virginia Woolf); Hope Mirrlees (see above); Ray Strachey (historian of the women’s movement) and Alys Pearsall Smith (first wife of Bertrand Russell) who was involved in movements for women’s rights, temperance, better factory conditions, and higher education.

After graduating in 1910, Eileen Power won scholarships to pursue medieval studies at the Sorbonne and at the London School of Economics (L.S.E.) She returned to Girton in 1913 as Director of Studies. At that time, medieval studies in England focussed on “wars, dynasties and kings.” Power studied “the great mass of humanity” including medieval women who ran their own land-holdings and engaged in trade. Her 1922 book, Medieval People, is a classic of social history aimed at the general reader.

In 1921, Power returned to the L.S. E. as a lecturer, and ten years later was the chair of economic history there. She settled in Mecklenburgh Square and enjoyed an active professional and social life. An internationalist, she showed how the medieval cloth industry involved international trade. She worked with the well-known economic historian, R.H. Tawney. In 1921 she met a Russian born L.S.E. student, Michael Postan, known as “Munia”, who became her research assistant, collaborator and, in 1937, her husband. Power’s collaboration with her sister on a children’s history of England, and her lectures on the B.B.C., show her belief in sharing her work with everyday people.

In China, Eileen Power met Reginald Johnston, the former tutor of the last emperor, and was briefly engaged to him, but returned to England to take up her economic history chairship at the L.S.E. and subsequently to marry Munia Postan. During the 1930s, with aggressor nations seizing other nations’ territories, she deplored the idea of appeasement and signed petitions urging League of Nations intervention. She died suddenly of heart failure in 1940. Power authored over thirty books. The Wool Trade in English Medieval History was published posthumously in 1941. Medieval Women was reissued in 1975.

Dorothy L. Sayers (1893-1957), who lived in Mecklenburgh Square in 1920-21, was a graduate of Somerville College, Oxford. After college she held a variety of jobs, including school teaching, working for Blackwell’s publishing and writing advertising copy in London. Wade shares fascinating details about Sayers’ personal life. She had two affairs, one with novelist John Cournos, who scorned her interest in the mystery genre and then with a neighbour who turned out to be married and left her pregnant. The man’s wife befriended Sayers and found her a place to wait out her pregnancy so she wouldn’t have to divulge it to her family. Sayers’ son, born in 1924,was fostered by a cousin and grew up thinking that Sayers was his cousin. In 1926 Sayers married the writer, Mac Fleming, who eventually adopted her son. The child was happy and settled with her cousin, however, and never lived with them.

While many viewed mystery as a lowbrow genre, Sayers was no snob. At the same time, she realized that many mysteries were plot-dominated, and that a mystery novel need not be merely about who was killed and why. She wrote works that were literary as well as popular, addressing social issues, prioritizing investigation and featuring complex, multi-faceted characters. Her characters Lord Peter Wimsey and Harriet Vane, a detective couple with an egalitarian relationship, was new to the genre and reflected her feminism and her views of the ideal relationship. Wade regards the feminist mystery, Gaudy Night, as Sayers’ masterpiece.

Wade starts her book with a profile of H.D. (Hilda Doolittle, 1886-1961) which this reader found confusing and less well organized than subsequent chapters. H.D., an American imagist poet, memoirist and autobiographical novelist, lived in Mecklenburgh Square from 1916 to 1918 with her husband, Richard Aldington. Her roman à clef, Bid Me to Love, is based on her unfaithful husband, his lover, and characters who represent D.H. and Frieda Lawrence. Several of her other novels were about being torn between heterosexual and lesbian desire.

To Wade, H.D. is an example of a woman of the era who found an unconventional lifestyle that was beneficial to her work. After losing the baby she was expecting with Aldington, she subsequently had an affair with the composer, Cecil Gray, and in 1919 gave birth to their daughter, Perdita. Shortly after that she met the wealthy English novelist Bryher (Annie Ellerman) who remained her lover for the rest of her life, although both had other relationships. H.D. was part of a ménage à trois with Bryher and her first husband, Robert McAlmon, and again with Bryher’s second husband, Kenneth McPherson. These domestic and romantic arrangements provided H.D. with support to pursue her writing and her analysis with Sigmund Freud.

Since so much has been written about Virginia Woolf, Wade focuses on the famous author’s life and work during the Phony War and the Blitz. In August 1939, Virginia and Leonard Woolf moved from Tavistock Square to Mecklenburgh Square, where they set up the Hogarth Press in the basement. They spent most of their time at their country cottage in Rodmell, Sussex, and when their Mecklenburgh Square house was demolished by a bomb in 1940, moved what they could salvage back to Rodmell.

Woolf committed suicide by drowning in 1941. While many accounts of Woolf’s life start with her suicide and go backwards into her earlier experiences, searching for signs that she was heading in that direction, Wade points out that during her last year, Woolf achieved much in her writing and was full of projects and plans. She finished her autobiography of Roger Fry, joined the Rodmell Women’s Institute and took part in plays, and wrote her last novel, Between the Acts. This novel, about the writing and staging of a village pageant depicting the history of England, presents an alternate history focussed on culture, woman and community.

Wade concludes by describing her own emotions and sensations while wandering through Bloomsbury. “There are pockets of the city where we can recall a radical past,” she writes, “and Mecklenburgh Square is one of these.” Kudos to her for bringing the achievements of these five women into the light again.

About the reviewer: Ruth Latta’s most recent novel is Votes, Love and War (Ottawa, Baico, 2019, info@baico.ca