By Daniel Garrett

James Baldwin, The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction 1948 – 1985 (St. Martin’s/Marek, 1985)

James Baldwin, The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction 1948 – 1985 (St. Martin’s/Marek, 1985)

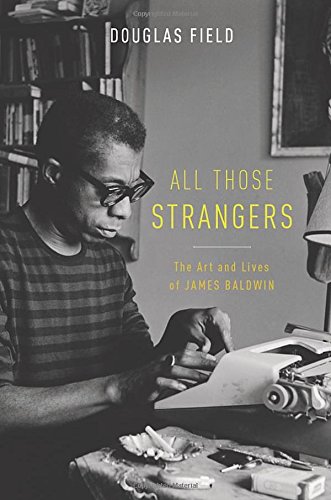

Douglas Field, All Those Strangers: The Art and Lives of James Baldwin (Oxford University Press, 2015)

In the essay “The Creative Process” (1962), published anew in the massive 1985 collection The Price of the Ticket, James Baldwin talks about the experiences and events that recur in every life, the timeless themes, that every artist, intellectual, and writer must consider, birth and the struggle to survive and live and love, and the necessity of facing death, with the key being what is found in silence and solitude, amid the wilderness of the self: there, the artist begins to discover what is true; and out of consciousness and craft, with dedication and discipline, he or she pursues the privilege and responsibility of being an artist. We are just people—human—to ourselves; but become other by those who merely watch us, those different from us: and assumptions of elemental difference can lead to conflict, but art can show what we share. The writer James Baldwin (1924 – 1987), who took as his own subject self and society, and the press of personal principles against the constraint of convention, admired many artists, literary, musical, theatrical, and visual: among them, Chinua Achebe, Josephine Baker, Balzac, Ingmar Bergman, Albert Camus, Ray Charles, Chekhov, Bette Davis, Miles Davis, Beauford Delaney, Dickens, Dostoevsky, Geraldine Fitzgerald, Henry Fonda, Aretha Franklin, Billie Holiday, Lena Horne, Mahalia Jackson, Louis Malle, Michelangelo, Toni Morrison, Harold Norse, Gordon Parks, Rembrandt, Sidney Poitier, Shakespeare, Nina Simone, Bessie Smith, Francois Truffaut, and Richard Wright. Prominent in Baldwin’s pantheon was Henry James, the author of such fine writing as The Ambassadors, The Golden Bowl, The Portrait of a Lady, The Tragic Muse, Washington Square, and What Maisie Knew. Henry James was an exemplar of what it meant to be an artist: “The artist is distinguished from all the other responsible actors in society—the politicians, legislators, educators, scientists, et cetera—by the fact that he is his own test tube, his own laboratory, working according to very rigorous rules, however unstated these may be, and cannot allow any consideration to supersede his responsibility to reveal all that he can possibly discover concerning the mystery of the human being,” Baldwin wrote in “The Creative Process” (The Price of the Ticket; page 670).

The realm of literature may be vast, its substances and strategies multiple, but literature is still a very particular and peculiar—imaginative, intuitive, as well as intelligent—apprehension, or perception, of the world, creative and interpretive, oriented to the emotional and social more than the scientific or structural; and Henry James (1843 – 1916) was among the most original and peculiar of writers, an eccentric master, strange to American culture and necessary for it. With Baldwin’s friend and colleague David Adams Leeming, Baldwin discussed the work and influence of Henry James for the Fall 1986 (Volume 8, Number 1) issue of The Henry James Review. (Leeming and Baldwin had met in Istanbul, as Baldwin was finishing Another Country, which Baldwin wrote in 1961 and published in 1962, with an opening epigram from Henry James.) David Leeming, who taught in Istanbul and later at the University of Connecticut, had studied Henry James with the great scholar Joseph Leon Edel; and James Baldwin considered Henry James key to Baldwin’s own aesthetic development: both Henry James and James Baldwin dramatized the importance and difficulty of recognizing self and other. Baldwin, who had been born in America but arrived in Paris young, with a one-way ticket and forty dollars in his pocket, thought Americans were sincere but without understanding, often mistaking what was material with what had meaning; and in The Henry James Review (Fall 1986), Baldwin told Leeming that Henry James captured the American inability—adolescent, dishonest, selfish—to perceive the reality of others, and the forfeiting of genuine joy. Baldwin examined how innocence and freedom work as ideals in American mythology, a mythology sometimes taken for truth: Baldwin found that one has to give up innocence to be free, to live. Henry James and James Baldwin, despite their criticisms of America, and even while living abroad, felt compelled to go on considering the complexities of America—complexities Americans themselves could deny. Both men knew, as Leeming observed and concurred, that the community, the village, is not the world, but that in losing ties to one’s village one can lose everything. Baldwin thought of creativity, like love, as being beyond ideology and yet with social roots and resonances; and both creativity and love required courage. I, like many other people, have returned to James Baldwin and his literature, drawn not only by memory of his passion and power but by the new publicity of films and books inspired by Baldwin, such as Barry Jenkins’s adaptation of Baldwin’s If Beale Street Could Talk.

I had not liked James Baldwin’s novel If Beale Street Could Talk (The Dial Press, 1974; Vintage International, 2006), his story about a young couple in love, Fonny and Tish, separated by a false charge of rape against the young man, a sculptor, in a society that did not expect much of him, a situation that inspires rage and sorrow. Its tone seemed vulgar, violent; and I suppose Baldwin, who was born in Harlem and died in France, was writing against the illusions of American culture—the assumptions of happiness, justice, and wisdom. I was surprised that Barry Jenkins, the director of the films Medicine for Melancholy (2008) and Moonlight (2016) had chosen to take that Baldwin text as a source for his work: yet Jenkins created a film, If Beale Could Talk (2018), acclaimed for its beauty, intimacy, passion, and truth. Barry Jenkins, like Robert Guediguian, the French film director who adapted Beale Street in 1998 as Where the Heart Is (A la Place du Coeur), saw in the book what I could not. Jenkins’s film has been part of a resurgence of interest in Baldwin and his oeuvre: after David Leeming’s James Baldwin: A Biography (1994), with its portrait of a Baldwin both fierce and fragile, and Magdalena Zaborowska’s inquisitive and informative study James Baldwin’s Turkish Decade: Erotics of Exile (2009), there have been, among other books, the Challenging Authors anthology James Baldwin, edited by A. Scott Henderson and P.L. Thomas (Sense Publishers, 2014), collecting commentary on Baldwin and the international scene and literary history, theatrical drama, personal transformation, and political change; and the impressive All Those Strangers: The Art and Lives of James Baldwin by Douglas Field (Oxford University, 2015); and Who Can Afford to Improvise? James Baldwin and Black Music, the Lyric and the Listeners by Ed Pavlić (Fordham University Press, 2016). Raoul Peck’s documentary I Am Not Your Negro (2016) presented Baldwin’s participation in the African-American civil rights movement of the 1960s and his relation to Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and Medgar Evers, an instructive and invigorating work for those less familiar with Baldwin; becoming like the older Karen Thorsen documentary James Baldwin: The Price of the Ticket (1989), which took its title from a retrospective anthology of Baldwin essays, an important visual repository of Baldwin’s vibrant presence—honest, intelligent, sensitive, and witty.

I suppose our interpretations of writers and their works have as much to do with who we are as people, and as readers, as with the articulations, gestures, and visions of writers, although that is something we may be reluctant to admit. While he lived, James Baldwin was ambitious for American culture and for his work within and beyond that culture, and he fulfilled and frustrated to different extents the expectations of others for art and politics. Since Baldwin’s death, there have been celebrations and critiques of his work, with a great deal of attention given to biology and biography and their influence on his texts and less exploration of his philosophy, principles, and purposes. One sees again the discovery of limits rather than range in interpretations of his work. I, as a reader and writer, as well as a citizen interested in social progress, was impressed, almost always, by Baldwin’s determination to bring eloquence, compassion, and wisdom to the hostilities and hopes he perceived, beyond the controversies of lasting conflicts—but I noted, as did others, that, with time’s passage, his disappointments inspired him to a brutal bluntness that could be read as bitterness. James Baldwin had lived through the murders of men he admired, such as Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr; and Baldwin, more and more, observed a culture that preferred the shallow to the serious—and saw that rhetoric, an attempt to bridge space, time, and experience with language, even his rhetoric, could not change reality. Who reads Baldwin and sees his complexities? Can that be found in the books, films, and talk focused on him by others, some of which explicate obvious subjects such as race and sexuality, and some of which attempt to identify the nature of his home life and relationships? The most generous view that one might have of the personal investigations of James Baldwin is that they are not merely gossipy, small-minded, speculative, and voyeuristic but attempts to find the man within the legend. I am inclined to return to his essays, and to Baldwin’s fiction—particularly to Another Country and Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone (in which friendship and love, especially regarding bisexuality and interracial relations, are allowed, challenged, and expanded)—and even his plays and poetry, to know his mind, to ascertain his understanding. James Baldwin’s The Price of the Ticket is a compendium of commentaries, of essays and reviews and letters and notes. The subjects are Harlem, Atlanta, France, Switzerland, literature, film, music, education, history, politics, national and racial identities, language, and more. Literature may survey all but it does not recognize every detail, just as law or science, philosophy or religion, may concern itself with all—with human existence and its chaos and confusions, its nature and its imposed logic within a larger cosmos—but each discipline sees all from a very specific perspective and using very specific language; and I relished Baldwin’s comparatively broad view. I liked, and like, contemplation—philosophy, literature and the arts, and practical prospects for positive political change; and I appreciated that Baldwin’s range of subjects went beyond the predictable. I sometimes think that James Baldwin had an intellectual freedom in his essays that he may not have had in his fiction, although he wrote fiction about the personal lives of Americans, black and white, male and female, gay and straight, observing their differences and similarities and the categorical lines that blurred. I sometimes think of his essays as intellectual and public and his fiction as personal and more emotional, narrower in focus; but, of course, his concerns and techniques varied.

James Baldwin, born to Emma Jones, a single mother, and reared by her and his stepfather, the disapproving and often raging David Baldwin, was a poor queer black boy who became an avid reader, lover of movies, teen Pentecostal minister, DeWitt Clinton High School graduate, and soon and finally a celebrated literary artist and controversial political activist: Baldwin challenged received ideas of religion and class, race, gender, and sexuality, and he wrote about the conflicts within families, the differing expectations for life and love of men and women, the inarticulate yet intense needs of children, the fear of both isolation and intimacy in young adults, the appeal and taboo of bisexuality, the power and hypocrisy of social rank, the desperate grasp of ambition, the rage beneath insistent American friendliness, the wanton immoralities of a puritanical nation, the willed ignorance of the personal turmoil of others, the transmutation of creativity into business, contradictions in law and injustice, and crimes that went unrecognized and unpunished. James Baldwin talked about the disfiguring power of categorization and conformity in society; and he created work—essays and reviews, fiction, drama, and poetry—that interrogated the clichés and conformities and he offered alternative ways of perceiving and being. Baldwin compelled many of us to see the damage done, its public and private cost. “It is the peculiar triumph of society—and its loss—that it is able to convince those people to whom it has given inferior status of the reality of this decree: it has the force and the weapons to translate its diction into fact, so that the alleged inferior are actually made so, insofar as the societal realities are concerned. This is a more hidden phenomenon now than it was in the days of serfdom, but is no less implacable. Now, as then, we find ourselves bound, first without, then within by the nature of our categorization,” Baldwin declared in the essay “Everybody’s Protest Novel” (1949) in The Price of the Ticket (page 32).

James Baldwin’s own work seemed most moving to me when he explored the connections rather than the conflicts between people—and when Baldwin spoke of the books, music, or even films that he loved or the people he respected. Baldwin could capture what made a boy or girl, woman or man, beautiful, troubled, unique. Something of his that I never forgot was about a conference in France—while Baldwin did not agree with all he heard there, I got a sense of the brilliance of the assembled black men, cosmopolitan, brave, and imaginative, men committed to a future more generous than the past. In Baldwin’s report, entitled “Princes and Powers” (1957), on the Negro-African Writers and Artists conference at the Sorbonne in September 1956, a gathering organized by Senegalese writer Alioune Diop, the founder of Presence Africaine, James Baldwin observed the contributions of participants such as Leopold Senghor, Aime Cesaire, George Lamming, Cheikh Anta Diop, and Richard Wright (Native Son and Black Boy), the last of whom had helped Baldwin get a fellowship. Leopold Senghor spoke of the arts as immersive and ordinary, as both form and spirit—a spirit that infused daily life; and Senghor caused Baldwin to consider the role of the artist in society, and further to wonder “What is a culture? This is a difficult question under the most serene circumstances—under which circumstances, incidentally, it mostly fails to present itself.” Then Baldwin began to wonder, “Is it possible to describe as a culture what may simply be, after all, a history of oppression?” (“Princes and Powers,” The Price of the Ticket; page 49). That—Baldwin’s question, if accepted as an answer—would seem to most to be an impoverished view of culture, I suspect—as many would identify culture as the relationships and rituals, the institutions and principles, the arts and entertainments, and the daily habits and styles of survival of a people. James Baldwin would note as well Senghor’s identification of the American writer Richard Wright with Africa (Senghor suggested Wright’s biography was a chapter in African history); and poet Aime Cesaire’s comment on the material roots of culture and the disturbing impositions of foreign powers in African affairs; Cheikh Anta Diop’s claims of Egypt as Negro; and Richard Wright’s own affirmation of individuality, science, and political progress. Those artists, intellectuals, and political leaders illuminated the complexities of Africa and its diaspora.

James Baldwin is often remembered for his commentary on race and sexuality, although his thinking touched on a variety of experiences and fields of knowledge. Baldwin, among other things, challenged a narrow view of sensuality and sexuality. He was not predictable: whereas, I, like more than a few people, have admired Andre Gide for his creative literature, and for attacking prejudice against homosexuality in Corydon (1920), marshalling as evidence the facts of biology, history, and culture, Baldwin criticized some of the work of Andre Gide, in response to the publication of the married Gide’s memoir Madeleine (1952). In Baldwin’s review “The Male Prison” (1954), also known as “Gide as Husband and Homosexual,” Baldwin said that Andre Gide should have been more scientific and less romantic when discussing homosexuality, but Baldwin rejects the evidence of civilization and nature that Gide presents in defense of homosexuality: “He ought to have leaned less heavily on the examples of dead, great men, of vanished cultures, and he ought certainly to have known that the examples provided by natural history do not go far toward illuminating the physical, psychological, and moral complexities faced by men. If he were going to talk about homosexuality at all, he ought, in a word, to have sounded a little less disturbed” (“The Male Prison,” The Price of the Ticket; 102). Is that an assertion, an opinion, rather than an analysis? What, in the matter of sexuality, could being scientific mean, if it does not refer to civilization or nature? Was Baldwin’s pose of sophistication, here, false? Is Baldwin discomforted by Gide’s direct confrontation? Had Baldwin thought through what an organized critique of heterosexualism would look like? Was Baldwin’s aversion to systematic thinking the cause of his critical response to both Richard Wright and Andre Gide?

Where are philosophy, principle, and profit to be found? James Baldwin had resisted the attraction of ideology, but he was forced to face the difficulties that inspired ideology: the pain and politics of people’s lives, the daily procedures—discriminatory and disrespectful, exploitive and exclusionary—that affected education, employment, housing, and justice, creating a culture of persecution; and, as the civil rights movement continued, Baldwin visited the American south, observing first how moving and visionary Martin Luther King Jr. was as a leader, and, later, the public criticism of King that begins to emerge as the movement is frustrated and does not achieve its goals quickly enough; and Baldwin began to expand his view of leadership: “The role of the genuine leadership, in its own eyes, was to destroy the barrier which prevented Negroes from fully participating in American life, to prepare Negroes for first-class citizenship, while at the same time bringing to bear on the Republic every conceivable pressure to make this status a reality. For this reason, the real leadership was to be found everywhere, in law courts, colleges, churches, hobo camps, on picket lines, freight trains, and chain gangs, and in jails. Not everyone who was publicized as a leader really was one. And many leaders who would never have dreamed of applying the term to themselves were considered by the Republic—when it knew of their existence at all—to be criminals” (“The Dangerous Road Before Martin Luther King,” 1961, in The Price of the Ticket; page 258). James Baldwin saw how the ruled and the rulers diverged in what they considered values and virtues—and how what was heroic (and necessary) to one was criminal to the other.

Whereas Baldwin had found transformation and transcendence in literature and art, the masses required more practical deliverance: Baldwin had found hope in the example of Richard Wright, a writer of stories, novels, and memoir, but Wright thought political consciousness and activism were essential in both life and art. In the three-part article, “Alas, Poor Richard” (1961), on Richard Wright (1908 – 1960), James Baldwin examines Richard Wright’s book Eight Men, a collection of stories, some of which Baldwin admires very much; and Baldwin recalls their friendship and the artistic disagreement they had about the purposes of art and black literature; and Baldwin goes further to speculate about Wright’s personal attitudes toward Africans and black Americans. Baldwin dares to enter into Wright’s mind in a way no respectable historian or journalist would—it’s a shocking arrogance and slander (his assertions are gossipy and petty, appearing malicious, what typically would be called lowdown). Yet, one of the most disagreeable assertions occurs when Baldwin says of Wright, “I was always exasperated by his notions of society, politics, and history, for they seemed to me utterly fanciful. I never believed that he had any real sense of how a society is put together” (The Price of the Ticket; page 271). James Baldwin had charm as a writer and focused on intimate relations in a way that many can relate to, but if one compares the social vision in both Baldwin’s fictions and essays to that in Wright’s fiction and commentary, it would seem clear who was most articulate about the institutions and powers that shape society. (The book The Politics of Richard Wright: Perspectives on Resistance, edited byJane Anna Gordon and Cyrus Ernesto Zirakzadeh, published by the University Press of Kentucky in late 2018, discusses Wright’s philosophy.) Richard Wright recognized that society is an amalgam not merely of people but of systems (thus, Wright was attracted to communism as a critique of capitalism, but rejected communism when it did not accept enough of human realities); whereas Baldwin often made it seem and sound as if society were no more than attitudes and impulses, and love and hate, and the absence or presence of compassion. Sometimes in James Baldwin’s work there is an assumption of knowledge that is not demonstrated or proven. Baldwin makes slighting comments about American presidents, and presidential gestures he would prefer or disapprove, for instance, but says little to nothing about their philosophies or policies. Baldwin tends to refer to attitude and emotion rather than institutions or policies; and he moved, slowly, novel by novel, from Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone (1968) to If Beale Street Could Talk (1974) to Just Above My Head (1979), to suggesting the nature and use of communities and institutions.

Baldwin recognized what was singular—a person, place, or thing. He, more often than not, saw character and content; and he tried to keep in mind what was still beautiful about us despite our ruin, our strengths despite our defeats. Baldwin saw the truth of the society by looking at the person. “That victim who is able to articulate the situation of the victim has ceased to be a victim: he, or she, has become a threat,” Baldwin writes in his film commentary The Devil Finds Work (1976), discussing the discrepancies between the Doubleday book Lady Sings the Blues (1956), Billie Holiday’s memoir as told to William Dufty, and the film Lady Sings the Blues (1972), directed by Sidney Furie and starring Diana Ross as Holiday (Baldwin thought, of course, the book contained more candor than the film). A work examining mythology and meaning in public representations, the book The Devil Finds Work, contains comment on old Hollywood films starring Henry Fonda, Bette Davis, and Joan Crawford, as well as newer films such as The Godfather and The Exorcist; and I was pleased to have Baldwin comment there on someone I liked, Diana Ross, just as I would appreciate Baldwin’s subsequent mention of Michael Jackson in his essay on masculinity, “Here Be Dragons” (1985). Billie Holiday, like Bessie Smith and Ray Charles and Aretha Franklin, was among the musicians James Baldwin most admired: Baldwin recognized Holiday’s pain but saw her as a triumphant artist—as a woman who bore witness to truth. Holiday’s testimony compelled the listener to question her circumstances. “The victim’s testimony must, therefore, be altered. But, since no one outside the victim’s situation dares imagine the victim’s situation, this testimony can be altered only after it has been delivered, and after it has become the object of some study. The purpose of this scrutiny is to emphasize certain striking details which can then be used to quite another purpose than the victim had in mind. Given the complexity of the human being, and the complexities of society, this is not difficult,” wrote Baldwin (The Devil Finds Work in The Price of the Ticket; page 628).

In The Price of the Ticket, James Baldwin—with simplicity—discusses some of his earliest personal relationships in the rambling essay “Here Be Dragons” (1985) which had been called once, “Freaks and the American Ideal of Manhood.” In his previously published work, James Baldwin had been discreet—protecting his dignity and freedom—but suggestive about his private life, sometimes more precise than at other times; and Baldwin, like more than a few men and women, had a bisexual past that many people have trouble understanding or even recognizing and remembering. In “Here Be Dragons,” Baldwin talks about his loneliness and poverty and his sexual adventures as a young man. There are facts that are surprising and some that are not surprising at all: “Yet I was, in peculiar truth, a very lucky boy. Shortly after I turned sixteen, a Harlem Racketeer, a man of about thirty-eight, fell in love with me, and I will be grateful to that man until the day I die. I showed him all my poetry, because I had no one else in Harlem to show it to, and even now, I sometimes wonder what on earth his friends could have been thinking, confronted with stingy-brimmed, mustachioed, razor-toting Poppa and skinny, popeyed Me when he walked me (rarely) into various shady joints, I drinking ginger ale, he drinking brandy” (“Here Be Dragons,” The Price of the Ticket; page 681). Is that—gratitude for being at 16 the object of a 38 years-old man’s sexual attention—merely a positive spin given to confusion and exploitation, to abuse? Was that a corruption of spirit and values; or a true liberation? Baldwin describes, as well, working in Manhattan’s Garment Center and visiting the 42nd Street library, Bryant Park, the movies, and Greenwich Village; and he met masculine men, often with wives or girlfriends, who were hostile in daylight and solicitous at night. Baldwin’s comments seems diaristic, the mere stating of fact rather than theory or even insight: “At the same time, I had already been sexually involved with a couple of white women in the Village. There were virtually no black women there when I hit those streets, and none who needed or could have afforded to risk herself with an odd, raggedy-assed black boy who clearly had no future. (The first black girl I met who dug me I fell in love with, lived with and almost married. But I met her, though I was only twenty-two, many light years too late.),” Baldwin states in “Here Be Dragons” (The Price of the Ticket; page 685). What is known of the woman Baldwin loved—what has she to say of that time? Was Baldwin a generous and thoughtful person, a good friend, an attentive lover, a prospective husband? Did he share his ambitions, his work? How deep, or how shallow, was the connection?

With so public and vivid a personality as James Baldwin, it becomes easy to wonder about matters that may not be one’s business at all. In Magdalena Zaborowska’s James Baldwin’s Turkish Decade (Duke University Press, 2009), focused on the time Baldwin spent in Turkey during the 1960s (specifically, from 1961 through 1971), and in her book on Baldwin’s house in St. Paul de Vence, Me and My House: James Baldwin’s Last Decade in France (Duke University Press, 2018), there are more reported scenes of his personal life, of his friends and male lovers, than one received of his private activities while Baldwin lived. Being in Turkey allowed Baldwin to step away from the usual dichotomies and oppositions in the world and in his life; and he made friends there and found inspiration. Magdalena Zaborowska discusses his work in Turkey on the novel Another Country (1962) and his direction of a well-received production of John Herbert’s theatrical play about prison life, Fortune and Men’s Eyes, in 1969; and the book James Baldwin’s Turkish Decade, impressive and rare, offers a plenitude of photographs to convey what that place and time were like. I tend to prefer books such as Ed Pavlić’s Who Can Afford to Improvise? James Baldwin and Black Music, the Lyric and the Listeners (Fordham University Press, 2016) and Douglas Field’s All Those Strangers: The Art and Lives of James Baldwin (Oxford University Press, 2015). Whereas Field attempts to be comprehensive, while focusing on significant facts, poet and professor Ed Pavlić takes Baldwin’s love of music as an organizing tool for his own study: Baldwin’s great affection for spirituals and blues, jazz, and soul are the lens through which Pavlić, an instructor at the University of Georgia, reads—with delicacy, insight, and force—Baldwin’s published work, as well as letters and manuscripts yet to be published, and Pavlić considers signal events in Baldwin’s life, such as the publication of the political commentary The Fire Next Time(1963), and Baldwin’s participation with Ray Charles in a Carnegie Hall concert (“The Hallelujah Chorus,” 1973) ). Ed Pavlić ruminates on the music artists Baldwin loved—Billie Holiday and Dinah Washington—and those Baldwin might have come to love had he lived longer, including Amy Winehouse. “Baldwin’s valences of listening emphasize a subtle and very powerful distinction in the deep structure of black language, culture, and black music most of all,” introduces Pavlić (Who Can Afford to Improvise?; page 9). Pavlić notes Baldwin’s sense of irony, his understanding of black anger—fury born of frustrated hopes for fulfillment as citizens—as expressed in fights and riots (Baldwin thought the violence of whites was born of terror, of fear of change and retribution); and Baldwin’s attempt to communicate with people such as Bobby Kennedy, who did not understand that African-American experience and expected gratitude for small advances and gestures. The intensity of pain and pleasure in black music, then, is to be expected, but it is, often, a surprise for other people. Baldwin saw beyond detail and detritus to depths: In Baldwin’s essay “The Uses of the Blues” (1964), Ed Pavlić writes, Baldwin can “differentiate between the hard-won reality he’s naming and the mythology that surrounds and threatens it. When pursued by attempting to elude the facts of life—whether via self-denial, inveterate moneymaking, or whatever else—happiness accrues in a register of experience that, for Baldwin, simply isn’t real” (38). James Baldwin admired the pianist and singer Ray Charles as a great tragic artist, a man of dignity, feeling, and skill, one who affirmed the facts of life; but when Baldwin and Charles appeared together on the same program, scheduled to feature a conversation between the two men, and musical performances by Charles alone and with his group, and readings from Baldwin’s story of a jazzman, “Sonny’s Blues” (1957)—which all sounds interesting to me—there were observers who found the pairing strange. “The reviews of ‘The Hallelujah Chorus’ may or may not have been meant to destroy, but they would hurt,” states Pavlić (165). Each artist is thought to belong to a particular box and brand, but that perception was fought, in different ways, by both Charles and Baldwin.

James Baldwin was admired by Mary McCarthy, William Styron, Richard Rorty, Michael Thelwell, and many other artists, intellectuals, and writers. James Baldwin’s work can seem ambiguous and complex, brilliant, determined, dialogical, and, in its pursuit of human difficulties metaphysical and mundane, even flawed; his work can seem less fixed, less complete, than the more metaphorical or methodical work of other writers such as Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, or Toni Morrison, and yet Baldwin’s work can feel more alive, more contemporary—as if Baldwin is speaking directly to us, speaking for our ears, speaking to our consciences and hearts. Baldwin has inspired devotion and denunciation:

“Another Country by James Baldwin should perhaps be judged as a document and not a novel. It is hard to believe that Baldwin, with his talents, could himself take it seriously as a piece of fiction. Its characters have a fitful reality; on the same page they can be in one phrase genuine and, in the next, false and lifeless. The style is alternately fierce, free, dramatic or arty, foolish, empty…Baldwin is genuine and admirable when he expresses rage or indignation and not at all convincing when he writes of love and tenderness. In this novel all the important questions, and they are many, are translated into sex. Truth and honor, indignation, love and hate, the injustices of American society, the menacing and explosive social conflicts for which there is no acceptable apology—the situation of the Negro in America is a scandal—all these matters are connected by Baldwin to the sexual theme.”

—Saul Bellow, “Recent Fiction: A Tour of Inspection” (1963), There Is Simply Too Much to Think About (Viking, 2015; page 189)

“If Beale Street Could Talk is Baldwin’s 13th book and it might have been written, if not revised for publication, in the 1950s. Its suffering, bewildered people, trapped in what is referred to as the ‘garbage dump’ of New York City—blacks constantly at the mercy of whites—have not even the psychological benefit of the Black Power and other radical movements to sustain them. Though their story should seem dated, it does not. And the peculiar fact of their being so politically helpless seems to have strengthened, in Baldwin’s imagination at least, the deep, powerful bonds of emotion between them. If Beale Street Could Talk is a quite moving and very traditional celebration of love. It affirms not only love between a man and a woman, but love of a type that is dealt with only rarely in contemporary fiction—that between members of a family, which may involve extremes of sacrifice.”

—Joyce Carol Oates, If Beale Street Could Talk review in the New York Times (May 19, 1974)

“I am about to confess something that literary critics should not confess: James Baldwin was literature for me, especially the essay.”

—Henry Louis Gates Jr., “An Interview with Josephine Baker and James Baldwin” (1985), The Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Reader (Basic / Civitas, 2012; page 559)

“You gave me a language to dwell in—a gift so perfect, it seems my own invention. I have been thinking your spoken and written thoughts so long, I believed they were mine. I have been seeing the world through your eyes so long, I believed that clear, clear view was my own.”

—Toni Morrison, “James Baldwin Eulogy” (1987), The Source of Self–Regard (Alfred A. Knopf, 2019; page 229)

“It’s a counterstatement. I wouldn’t have said that [Murray’s essay on James Baldwin in The Omni–Americans] if he were not there. What would I have said? I don’t know what I would have said! I had some conceptions but Baldwin brought it into some sort of focus. I said, ‘‘That ain’t the way that is. What is this? I can’t stand that! I’m not a victim. I never felt like a victim!’ I always thought I was smart, good-looking, and promising. That’s what I always thought. That’s what people always said, ‘Look at that honey-brown boy. He’s so nice. He’s so smart.’“

—Albert Murray to Greg Thomas, “Human Consciousness Lives in the Mythosphere” (1996), Murray Talks Music (University of Minnesota Press, 2016; page 88)

“One of the first books by a black writer I read came from my father’s bookshelf (a consistent reader, a critically thinking working man). It was James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time. I could not have asked for a better literary mentor than Baldwin—witty, radical, transgressive, a sexual renegade, he embodied it all.”

—Bell Hooks, “Against Mediocrity,” Writing Beyond Race: Living Theory and Practice(Routledge, 2013; page 161)

“Baldwin, for his part, accepted no characterization. ‘A real writer,’ he wrote, ‘is always shifting and changing and searching.’ The credo guided his work and his life. He moved to France at the age of twenty-four to avoid ‘becoming merely a Negro; or, even, merely a Negro writer.’ Later he would recoil whenever someone described him as a spokesman for his race or for the civil rights movement. He rejected political labels, sexual labels (‘homosexual, bisexual, heterosexual are twentieth-century terms which, for me, really have very little meaning’), and questioned the notion of racial identity, an ‘invention’ of paranoid, infantile minds. ‘Color is not a human or a personal reality,’ he wrote in The Fire Next Time. ‘It is a political reality.’

—Nathaniel Rich, “James Baldwin and the Fear of a Nation” New York Review of Books (May 12, 2016).

Critical appreciation of James Baldwin’s work has risen and fallen, fallen and risen; and the publication of Baldwin’s The Cross of Redemption: Uncollected Writings (Pantheon Books, 2010) ignited new attention, as have studies such as Lawrie Balfour’s The Evidence of Things Not Said: James Baldwin and the Promise of American Democracy (Cornell University Press, 2001); Lynn Orilla Scott’s James Baldwin: Later Fiction (Michigan State University Press, 2002); and James Baldwin: America and Beyond (University of Michigan Press, 2011), edited by Cora Kaplan and Bill Schwarz. Consequently, there have been conferences, lectures, talks, gallery exhibitions, films, and other signs of a significant legacy. I am not sure that I was all that impressed by Baldwin’s posthumously published The Cross of Redemption, edited by Randall Kenan, when I first read it, but I have returned to it again and again: it contains essays and reviews and speeches, profiles and letters and a small piece of fiction, featuring subjects that include the relation of the artist to mass culture, and literature, drama, film, boxing, freedom, language, history, war, colonialism, race, prison, and sexuality. Baldwin remarked, “We do not seem to want to know that we are in the world, that we are subject to the same catastrophes, vices, joys, and follies which have baffled and afflicted mankind for ages. And this has everything to do, of course, with what was expected of America: which expectation, so generally disappointed, reveals something we do not want to know about sad human nature, reveals something we do not want to know about the intricacies and inequities of any social structure, reveals, in turn, something we do not want to know about ourselves. The American way of the life has failed—to make people happier or to make them better. We do not want to admit this, and we do not admit it” (“Mass Culture and the Creative Artist,” 1959, in The Cross of Redemption; page 5). Baldwin wrote about the immorality of American power, internationally and domestically, and the subjugation of black Americans. He looked for hope. He paid tribute to Shakespeare, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Lorraine Hansberry, Sidney Poitier, Elia Kazan, Geraldine Fitzgerald, Angela Davis, and Bobby Seale. Yet Baldwin was aware, always aware, of the limits of the acceptance of artists and entertainers due to social prejudice: “The fact that Harry Belafonte makes as much money as, let’s say, Frank Sinatra, doesn’t really mean anything in this context. Frank can still get a house anywhere, and Harry can’t,” Baldwin said (on page 60) in “The Uses of the Blues” (1964), an article in which he went on to advise, “People who in some sense know who they are can’t change the world always, but they can do something to make it a little more, to make life a little more human. Human in the best sense. Human in terms of joy, freedom which is always private, respect, respect for one another, even such things as manners. All these things are very important, all these old-fashioned things” (66). A few years before he died, Baldwin wrote, “A Letter to Prisoners” (1982) and said, “What artists and prisoners have in common is that both know what it means to be free” (page 212); and writing to the South African bishop Desmond Tutu, “The Fire This Time: Letter to the Bishop” (1985), Baldwin noted that “there are revolutions and revolutions—to leave it at that. They are glorified in the past. They are dreaded and, insofar as possible, destroyed in the present” (page 217).

Douglas Field, a literature lecturer at the University of Manchester, affirms James Baldwin’s complexities, and explicates the life, work, and reputation of Baldwin in All the Strangers: The Art and Lives of James Baldwin: Douglas Field is a good writer and fair judge, and his is a careful exposition of Baldwin’s career and concerns, identifying and illuminating tensions between and among reason and passion, history and the present, religion and secularism, America and the world, and race and sexuality. “Baldwin’s repeated repudiations of theories, labels, and identity categories present a major challenge to literary critics and cultural historians who strive to place his work within a critical narrative,” acknowledges Field (All Those Strangers; page 8). Researcher and interpreter Douglas Field, aware of Baldwin’s lasting appeal and informed by the latest scholarship, looks at Baldwin’s relationship to personal identity and social caste, class analysis and movement politics, and the African diaspora and African-American exceptionalism. Field reminds us of Baldwin’s youthful interest in socialism and respect for Russian revolutionary thinker and writer Leon Trotsky, of Baldwin’s precocious professional development, writing for important magazines such as The Nation and The New Leader as a very young man, and of his investment in Greenwich Village bohemia, where Baldwin worked for a time in a Caribbean restaurant, in which he met the esteemed writers C.L.R. James, Alain Locke, and Claude McKay. James Baldwin had bright and influential Jewish friends, some of whom helped him to publish; but Baldwin was wary of the self-congratulations that could attend liberal politics. Mid-century American political paranoia led to official surveillance of writers such as Baldwin, who criticized American ideas of identity and justice in essays and fiction. Scholar Douglas Field reminds us how rare was the prominence and success of Baldwin and Langston Hughes, Richard Wright, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Ralph Ellison.

James Baldwin, like Richard Wright, had begun his career skeptical about the actual achievements of African-American literature, an attitude some resented. Baldwin’s allegiances were questioned when he wrote a novel, Giovanni’s Room (1956), without discernible black characters; and that book, like Gore Vidal’s The City and thePillar (1949) was controversial for its sexual candor: for the sexual fluidity, and homosexuality, of its lead (and quite masculine) American white male character; although the scenarios in both books were in line with the sociological findings of researcher Alfred Kinsey; and both books were, really, about arrested development—men who had not grown beyond an adolescent conception of self and love and sex. (Baldwin would be repudiated for his radical sexual ethos by some of the younger black activists.) Baldwin’s Another Country (1962) may have been more bold, more brave in its presentation of friendship, love, and desire, of bisexuality and interracial sex: “Although Baldwin was lambasted by critics who claimed that he extolled the power of love in AnotherCountry rather than offering concrete political solutions, I want to suggest Baldwin’s developing notion of love is key to an understanding of his life and work,” states Douglas Field (All ThoseStrangers; page 95). Love, for Baldwin, is a source of spirituality and social action as well as intimacy and joy. James Baldwin, who left much of organized religion behind without losing a sense of the holiness of humanity, yet expected human imperfection; thus, it is not a betrayal to explore, with respect, his; and, perhaps, such interrogation is an inevitable test for immortality. Baldwin evolved a rhetoric on race, a language of history, hyperbole, and parable, which would assert moral claims and pierce conscience, but that rhetoric began to freeze him in a grand pose of protest and poignant plea (evidence for that can be read in his published dialogues with Margaret Mead, Nikki Giovanni, and Audre Lorde). His rhetoric may have become reflexive—such a literary person may think only of his own belief and thought, his gifts and grace, not of his indulgences and limitations, his distortions—but even a typical listener or reader could recognize the peculiarity of Baldwin’s speech. Baldwin, too, sometimes missed small movements that became major changes (I cannot recall any significant statement from Baldwin regarding feminism or the gay liberation movement, banking deregulation or the increased use of computers, or degradation of the natural environment; and I wished that he had written more about independent art and international cultures). With James Baldwin’s late life teaching in American colleges and his return to observing the American scene withThe Evidence of Things Not Seen (1985), he might have begun to renew his vision and voice.

Giovanni’s Room (1956) is set in France; and Another Country (1962) has a long section located in France, Baldwin’s literary and personal refuge. Much of IfBeale Street Could Talk(1974) and Just Above My Head (1979) are set in Harlem, where Baldwin’s life began. He led a tumultuous life, and he tried to be loyal to his allegiances, to his communities, but he could not deny what he believed was true, nor his own desires. In his last two novels, Baldwin showed the connections—the knowledge, the sympathy, the sacrifice, as well as the idiosyncratic language and pleasures and styles—that some members of the black community shared and valued. Baldwin, when young, had doubted how strong some of the ties could be among African-Americans, and between Africans and African-Americans, but he would come to affirm those ties. “Baldwin’s last two novels, If BealeStreet and Just Above MyHead, are both love stories,” asserts Douglas Field (All Those Strangers; page 107); and, concludes Field, “My aim has not been to celebrate or romanticize Baldwin’s paradoxes or inconsistencies but to argue that much of his seemingly contradictory work begins to cohere when read in the context of the material reality out of which he lived and wrote from the 1940s to the 1980s” (147). The transformational and transcendent, as well as the transient and the tragic, can be read still in much of James Baldwin’s words, spoken and written: and books such as Decolonial Love: Salvation in Colonial Modernity by Joseph Drexler-Dreis (Fordham University Press, 2018) and James Baldwin and the Heavenly City: Prophecy, Apocalypse, and Doubt by Christopher Z. Hobson (Michigan University Press, 2018) examine Baldwin’s pursuit, and portraits, of the human being as special, as miraculous despite his or her inclination to disaster, and the consequent necessity of care and change in a world of conflicts and contaminations.

James Baldwin, like most of us, relished appreciation but he did not expect easy agreement, knowing that the purpose of an artist differed from that of the larger society: “Society must accept some things as real; but he must always know that the visible reality hides a deeper one, and that all our action and all our achievement rests on things unseen. A society must assume that it is stable, but the artist must know, and he must let us know, that there is nothing stable under heaven,” wrote Baldwin (“The Creative Process,” The Price of the Ticket; page 670). Baldwin’s writing, at its finest, gives us what we want and need; and, fundamentally, literature is fine writing: work that is creative and expressive, as well as analytical; and while we try to impose literature and other art with the standards of our own preferences—thinking of literature as that which organizes and trains the mind, articulating ideals, evoking worlds past, present, and future, and identifying dangers, offering compassion, inspiring community, and suggesting where joy and wisdom might be found, while giving us characters, situations, and stories we like and find interesting—literature is fine writing, often recognizable to both those who love and hate it.

Daniel Garrett is a writer whose work has appeared in the male feminist magazine Changing Men, and in The African, American Book Review, Black Film Review, Cinetext, Contact II, Film International, The Humanist, Hyphen, Illuminations, Muse Apprentice Guild, Offscreen, Option, Pop Matters, Quarterly Black Review of Books, Rain Taxi, Red River Review, Review of Contemporary Fiction, and Wax Poetics, as well as The Compulsive Reader.

A Reading List for a New Era

“Honor. He knew that he had no honor which the world could recognize. His life, passions, trials, loves, were, at worst, filth, and, at best, disease in the eyes of the world, and crimes in the eyes of his countrymen. There were no standards for him except those he could make for himself. There were no standards for him because he could not accept the definitions, the hideously mechanical jargon of the age. He saw no one around him worth his envy, did not believe in the cures, panaceas, and slogans which afflicted the world he knew; and this meant that he had to create his standards and make up his definitions as he went along. It was up to him to find out who he was, and it was his necessity to do this, so far as the witchdoctors of the time were concerned, alone,” wrote James Baldwin of Eric in Another Country. Eric, the doubted and slandered man, the bisexual man, is, actually, the most honorable man in the book: able and willing to love both men and women, Eric is alert, aware, and he listens, responds, nurtures. He reads his friends and associations. He grows and helps them to grow. How do we read, not only literature and art, but ourselves and those around us? How do we learn to look beyond appearance into mind and spirit? How do we take what we have learned and transform ourselves, transform the world? With quiet and attention and observation and listening and sensitivity and thought; and with careful effort, with the collaboration of others—as always; and there are works of surpassing excellence, very old and newer, that might assist us. Here, below, are some books of enlightenment and entertainment that might be of use, as well as offer significant pleasure. DG

African American Cinema through Black Lives Consciousness, edited by Mark Reid (Wayne State University Press, 2019). Essays by Melba Joyce Boyd, Dan Flory, James Smalls and other writers consider history and theory, and issues of race, class, gender, and sexuality as they appear and discourse in cinema.

American Audacity by William Giraldi (Liveright Publishing / W. W. Norton, 2018). Literary essays, including comment on James Baldwin, Harold Bloom, David Denby, Stanley Fish, Allan Gurganus, Herman Melville, Cynthia Ozick, Edgar Allan Poe, and Lionel Trilling.

American Poets in the 21st Century: Poetics of Social Engagement edited by Michael Dowdy and Claudia Rankine (Wesleyan Univ. Press, 2018). Poetry and its examination in prose, with regard to what is possible in society, in a book of acute attention and thought.

Angels on Toast by Dawn Powell, a fiction of greedy ambition and questionable relationships, funny and sharp (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1940; and Steerforth, 1998).

Another Country by James Baldwin (The Dial Press, 1962; and Vintage, 1992), a novel about friendship and love and ambition and defeat, a work of torment and thought and transcendence, regarding class, race, and sex.

Art of the Ordinary: the Everyday Domain of Art, Film, Philosophy, and Poetry, by Richard Deming (Cornell University Press, 2018), is an interdisciplinary look at sources of intelligence and insight.

The Autumn of the Patriarch (Plaza & Janes, 1975; and Harper Perennial, 2006) by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, about the appetite and power of a dictator, an all-encompassing and explosive portrait.

The B Word: Bisexuality in Contemporary Film and Television by Maria San Filippo (Indiana University Press, 2013).

Beloved by Toni Morrison (Knopf, 1987), a novel in which a mother’s terror, and determination to spare her children pain with no promise of its end, leads to a desperate and fatal act that haunts her

Bertolt Brecht on Film and Radio edited and translated by Marc Silberman (Methuen, 2000) features the philosophical and practical comments of a revolutionary artist and thinker.

Black Intellectual Thought in Modern America: A Historical Perspective, edited by Brian D. Behnken, Gregory D. Smithers, and Simon Wendt (University Press of Mississippi, 2017), has a diversity of commentators who look at the work of radicals and conservatives, male and female, past and present.

Black Power and Palestine: Transnational Countries of Color by Michael R. Fischbach (Stanford University Press, 2019), while recovering history, demonstrates that it is a gift of insight when brave but suffering people see themselves in the other’s experience and effort, finding compassion and comfort, strength and strategies.

The Chaneysville Incident by David Bradley (Harper, 1981), a novel of history and heroism, of exciting incidents and excellent insights as one man tries to decipher the long-hidden truth about his family and town.

Chekhov: Stories for Our Time, an anthology of amusing and melancholy tales by Anton Chekhov, translated by Constance Garnett, Ilan Stavans, and Alexander Gurvets, with a foreword by Boris Fishman (Restless Books, 2018).

Cinematic Encounters: Interviews and Dialogues by Jonathan Rosenbaum (Univ. of Illinois Press, 2018) reveals the personality, philosophy, and process behind many significant films, including those of Jim Jarmusch, Jacques Tati, and Orson Welles.

The Complete Poetry of Aime Cesaire by Aime Cesaire, translated by A. James Arnold and Clayton Eshleman (Wesleyan University Press, 2017), the verses of this great son ofMartinique—a great man, a great poet—in French with English translations.

Conversations with Percival Everett edited by Joe Weixlmann (University Press of Mississippi, 2013). Genius talking.

Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Dark Space: Architecture, Representation, Black Identity by Mario Gooden (Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2016). Can architecture express the spirit of a people? How does architecture represent history, while offering something of value to the present? Gooden’s thoughts on design are organized in challenging, complex essays, using completed sites as evidence.

Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes

Eric Rohmer: A Biography by Antoine de Baecque and Noël Herpe (Columbia University Press, 2016). The French director, the maker of some of the twentieth-century’s most intelligent and subtle films (Claire’s Knee and The Marquise of O), and an extremely private man, is given a thorough accounting.

Essential Essays: Culture, Politics, and the Art of Poetry by Adrienne Rich, edited by Sandra M. Gilbert (W.W. Norton, 2018)

Film Worlds by Daniel Yacavone (Columbia University Press, 2015). Films explore worlds—and create worlds. Films offer perspective—and change ours. Philosopher Yacavone explores such facts from a variety of angles.

Foucault at the Movies translated and edited by Clare O’Farrell (Columbia University Press, 2018). Michel Foucault, a radical thinker, in dialogue with worthy commentators, about film, with reference to culture, philosophy, and politics.

Gay Guerrilla: Julius Eastman and His Music, edited by Renée Levine-Packer, author of This Life of Sounds: Evenings for New Music in Buffalo, and composer and writer Mary Jane Leach (University of Rochester Press, 2015), is about a radical black composer, and features fully engaged writers such as David Borden, John Patrick Thomas, and Ryan Dohoney.

George Washington Carver by Christina Veilla (Louisiana State University Press, 2015), alsoGeorge Washington Carver: In His Own Words, edited by Gary R. Kremer (University of Missouri Press, 1991; 2017). Profile(s) of a great scientist and teacher, a truly unique man.

Global Africa: Into the Twenty-first Century edited by Dorothy L. Hodgson and Judith A. Byfield (University of California Press, 2017) offers a comprehensive survey of the many contributions, cultural and practical, of Africa, today and yesterday, to the world.

The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck

Great Expectations by Charles Dickens

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Green Documentary: Environmental Documentary in the Twenty-first Century by Helen Hughes (Intellect, 2014)

Half an Inch of Water: Stories by Percival Everett (Graywolf Press, 2015). Inventive, thoughtful short fiction—imaginative and realistic.

The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood

Herzog by Ebert (University of Chicago Press, 2017). Film critic Roger Ebert’s critical response to the work of filmmaker Werner Herzog, director of Fitzcarraldo and Aguirre, the Wrath of God.

Hitchcock’s People, Places, and Things by John Bruns (Northwestern University Press, 2019). Film commentary.

How History Gets Things Wrong: The Neuroscience of Our Addiction to Stories by Alex Rosenberg (The MIT Press, 2018)

How to See by David Salle (W.W. Norton, 2016), features the perceptions and philosophy of a popular and significant visual artist.

I’m Not Here to Give a Speech by Gabriel Garcia Marquez (Vintage Books, 2019). Marquez’s essays and speeches.

In a Shallow Grave by James Purdy (Arbor House, 1975), a book by an original writer, harrowing and witty, features war and its scars and repulsions, romance and its deceptions, friendships and their redemptions.

Indonesian Notebook: A Sourcebook on Richard Wright and the Bandung Conference edited by Brian Russell Roberts and Keith Foulcher (Duke University Press, 2016).

Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte

Jean Cocteau: A Life by Claude Arnaud (Yale University Press, 2016)

L.A. Rebellion: Creating a New Black Cinema edited by Allyson Nadia Field, Jan-Christopher Horak, and Jacqueline Najuma Stewart (University of California Press, 2015) works as a sourcebook on the cinema of Charles Burnett, Julie Dash, Zeinabu irene Davis,Jamaa Fanaka, Haile Gerima, and Billy Woodberry, all affiliated to one extent or another with California (specifically, the University of California).

Lord of the Flies by J.R.R. Tolkien

The Lost History of Liberalism: From Ancient Rome to the Twenty-first Century by Helena Rosenblatt (Princeton University Press, 2018)

Male Bisexuality in Current Cinema by Justin Vicari (McFarland, 2010)

Moby Dick by Herman Melville. Greatest of American novels—demanding. (Exact title is Moby-Dick)

Monument: Poems New and Selected by Natasha Trethewey (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt 2018)

Mostly Straight by Ritch C. Savin-Williams (Harvard Univ. Press, 2017). Sexual fluidity.

Native Americans on Film: Conversations, Teaching, and Theory edited by M. Elise Marubbio and Eric L. Buffalohead (University Press of Kentucky, 2013 / 2018)

The New Negro: The Life of Alain Locke by Jeffrey C. Stewart (Oxford University Press, 2018). Acclaimed biography of African-American philosopher of art, community, cultural pluralism, and black life.

Nineteen Eighty-Four / 1984 by George Orwell

New Perspectives on the Black Intellectual Tradition, edited Keisha N. Blain, Christopher Cameron, and Ashley D. Farmer (Northwestern University Press, 2018), considers African-American identity, culture, spirituality, politics, and international concerns.

Notes from a Black Woman’s Diary by Kathleen Collins (Ecco/Harper Collins, 2019). The fiction and scripts as well as diaries of exceptional but neglected and newly rediscovered writer and filmmaker Kathleen Collins (Losing Ground).

Old in Art School by Nell Painter (Counterpoint, 2018). How does the academy work? What are the true values of the art market? How can an older woman, an African-American woman, even a very accomplished and sophisticated woman, learn what she needs to know of history, philosophy, and skill to become a better artist while negotiating the…excrement?

On Freedom and the Will to Adorn: The Art of the African American Essay by Cheryl Wall (University of North Carolina Press, 2019)

Oxherding Tale by Charles Johnson (Grove Press, 1982). Slavery and freedom. Friendship and family and sex. Beautiful, thoughtful, funny—out of history, a timeless work of fiction.

Palestine: A Four Thousand Year History by Nur Masalha (Zed Books, 2018)

Perspectives on Percival Everett edited by Keith B. Mitchell and Robin G. Vander (University Press of Mississippi, 2013)

The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

The Portrait of a Lady by Henry James

The Presidency of Barack Obama edited by Julian E. Zelizer (Princeton University Press, 2018)

The Promise of Failure: One Writer’s Perspective on Not Succeeding by John McNally (University of Iowa Press, 2018)

Queen Bey: A Celebration of the Power and Creativity of Beyonce Knowles-Carter edited by Veronica Chambers (St. Martin’s Press, 2019)

Race and the Revolutionary Impulse in The Spook Who Sat by the Door edited by Michael T. Martin, David C. Wall, and Marilyn Yaquinto (Indiana University Press, 2018). Contemplation of legendary film.

The Romare Bearden Reader edited by Robert G. O’Meally (Duke University Press, 2019)

The Salt Eaters by Toni Cade Bambara (Random House, 1980). Communities, like personalities, fracture. What can heal them, move them toward purpose? This earthy novel of great vision.

Selected Poems, 1950 – 2012 by Adrienne Rich, edited by Albert Gelpi, Barbara Charlesworth Gelpi, and Brett C. Miller (W.W. Norton, 2018 / 2013)

The Selected Works of Edward Said by Edward Said (Anchor/Penguin Random House, 2019). Eloquent writer. Brilliant thinker. Valuable man. Wonderful book.

Six Turkish Filmmakers by Laurence Raw (University of Wisconsin Press, 2017), and The Routledge Dictionary of Turkish Cinema by Gonul Donmez-Colin (Routledge, 2013) offer great information for those interested in cinema in general and Turkish film in particular.

Sleeping with Strangers by David Thomson (Knopf, 2019). Sexuality (homosexuality and heterosexuality), overt and covert, in cinema.

Solitude and Company: The Life of Gabriel Garcia Marquez with Help from HIs Friends… by Silvana Paternostro (Seven Stories Press, 2019)

The Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway

Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston.

There Will Be No Miracles Here: A Memoir by Casey Gerald (Riverhead Books, 2018). The dark side of American ambition and success within a rigged and brutal system disguised by glamour and justified by platitudes.

Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe (Heinemann, 1958), the story of a young African, his village, and the confrontation with British colonialism; one of the novels that opened the eyes of the world to modern fiction from Africa.

To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

Trojan Women, Helen, Hecuba by Euripides (University of Wisconsin Press, 2016)

Under the Bisexual Umbrella: Diversity of Identity and Experience, edited by Corey E. Flanders (Routledge, 2019). Scholarship and theory.

War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy

We’re On: A June Jordan Reader edited by Christoph Keller and Jan Heller Levi (Alice James Books, 2017). The poetry and prose of a sensual, shrewd, and satirical writer.

White Teeth by Zadie Smith (Hamish Hamilton, 1999). Family, friendship, and love. Death and religion. Modern life. Multiculturalism. Television. Wit.

Wrong-Doing Truth Telling: The Function of Avowal in Justice by Michel Foucault, edited by Fabienne Brion and Bernard E. Harcourt (University of Chicago Press, 2014)

Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte