Reviewed by Ruth Latta

Reviewed by Ruth Latta

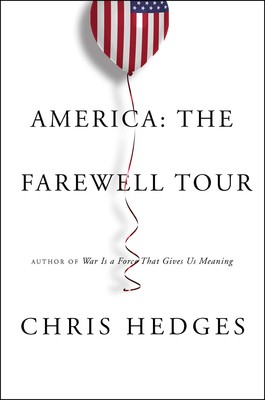

America: The Farewell Tour

by Chris Hedges

Knopf Canada

August 21, 2018, ISBN: 9780735275959, 400pages, hardcover

Chris Hedges is a professor, social critic, ordained Presbyterian minister, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, and a socialist. In his new book, America: The Farewell Tour, he contends that the United States is in decline. Random and mass shootings, proliferation of hate groups, the income gap between rich and poor, widespread use of opioids – these are some of the signs of a decaying civilization. Although in the course of writing this book, Hedges travelled in America to talk to people impacted by the current state of affairs, he is referring in the title, not to his own journeys as a reporter, but to America making its farewell tour as a great country.

Corporate capitalism, he declares, has erased liberty, equality and freedom in its pursuit of property. In its final stage, capitalism isn’t about manufacturing useful products, and isn’t based on competition and the free market system; instead, wealth is obtained by manipulating the price of currencies, stocks and commodities. Global corporations monopolize the world’s markets. The banking sector, the fossil fuel industry, the agriculture and food sector, the arms and communications industries, and others, prevent anyone challenging their international dominance. They push through trade deals that weaken governments’ ability to set environmental regulations and working conditions. The state is surrendered to the rich. President Trump and his cabinet are diminishing or dismantling government agencies and programs that they were supposed to administer. They deny that environmental disaster looms.

In Hedges’ first chapter, “Decay”, he visits Scranton, Pennsylvania, once the proud home of the Scranton Lace Company, a textile firm which employed thousands of unionized workers. But the financial crisis of 2008 combined with the closure of the factory, has almost bankrupted Scranton. Textile manufacturing has been moved to countries like Bangladesh, where workers are serfs paid around 32 cents an hour . American workers are laid off, and formerly vibrant American cities, without a tax base, are having to sell to private companies fundamental assets such as their water systems. They are also forced to slash the salaries of city employees, to lay people off, to cut city services and to increase taxes.

“After the last city assets are sold, what is next?” Hedges asks. “No one has an answer.” The only thriving industry in the Scranton area is an arms manufacturing company, heavily subsidized with public funds from the federal government.

Work, Hedges points out, is fundamental not only to putting food on the table, paying the rent and buying medical insurance, but also to a sense of purpose and a feeling of community and solidarity. People without work feel worthless and compensate for it with drug abuse, sexual violence (discussed in his chapter on “Sadism”), and gambling. They look for scapegoats and saviours. The reason the Democratic Party lost the Presidential election of 2016, says Hedges, is because it failed to offer a platform to help working people and the poor.

“A society in chaos celebrates the morally degenerate, cunning and deceitful,” says Hedges. “It is inevitable that for the final show we vomited up a figure like Trump.” Hedges compares him to the Emperor Nero who fiddled while Rome burned, or to the “feckless Romanovs” during the crumbling of Russia during the First World War.

In his chapter titled “Heroin”, Hedges interviews recovering addicts and bereaved families. In turning to opioids, drug users are trying to find the “affirmation, warmth and solidarity” that should come from family, friends and communities where they could find purpose and identity. “Corporate capitalism,” he comments, “has made war on the communal and sacred, on those forces that allow us to connect and transcend our temporal condition to bond with others.”

In “Work”, Hedges builds on themes in “Decay”, noting that three quarters of suicides are men. A combination of unemployment, marriage failure, loss of social cohesion and declining health are to blame. Since the 1970s, society has become less structured, with fewer people attending church, no more guarantees of following your father into a unionized manufacturing job, and a movement away from marriage toward other “socially acceptable ways of forming intimate partnerships or rearing children.” For some people, such changes are liberating, but when they fail, the individual often blames himself. Hedges quotes the philosopher Emile Durkheim who said that man must attach himself to a purpose that is greater than himself and which outlives him. Life is only tolerable if one can see some purpose in it.

Hedges sees little hope for the church as a vehicle of social change. The liberal churches, he says, hold up multiculturalism and identity politics as their main concern, while ignoring economic and social justice. Meanwhile, fundamentalist churches preach that prosperity is a sign that one is right with God.

In the chapter on “Work”, Hedges offers the story of Eugene B. Debs as inspiration. An American socialist/activist who died in 1926, Debs was a union leader imprisoned for his role in the historic Pullman Strike. Debs was released in 1895 and founded the Socialist Party of America and the International Workers of the World (IWW) He helped elect socialist mayors in seventy cities and in 1912 got two socialists elected to Congress. He ran for the U.S. Presidency five times between 1900 and 1920. As well as advocating nationalization of banking and transport, women’s suffrage, and an end to Jim Crow laws and lynching, Debs called for a social safety net including old age pensions and unemployment insurance. He got in trouble in 1918 when he denounced American participation in World War I, claiming that it was a capitalist war in which the working class was being used as cannon fodder, and denouncing the Wilson administration’s persecution of anti-war activists, trade unionists and socialists.

Many, like Debs, worked for a more equal society, and through their efforts, gains were made; however, in recent decades the hard-won rights of workers have been stripped away. “We have to begin all over again,” says Hedges, “…understanding that we can only pit power against power. Our power comes only when we organize.”

In “Gambling”, Hedges traces the rise and fall of the Trump Taj Mahal in Atlantic City, showing it to be a microcosm of what’s happening in America generally. He quotes a New YorkTimesarticle titled, “How Donald Trump Bankrupted his Atlantic City Casino but Still Earned Millions.”

Hedges says in his final chapter, “Freedom”, that we are now in an “interregnum”, an era in which the reigning ideology has lost effectiveness but has yet to be replaced by a new one. The death blow to the American empire, he says, will come when the dollar is no longer the worldwide currency standard. When that happens, the economy will contract, U.S. Treasury bonds will be worthless, and the United States will no longer be able to maintain its global military power. The global vacuum will probably be filled by China, or perhaps a coalition of transnational corporations, military organizations like NATO and an international financial leadership “self-selected” at Davos.

Hedges believes there are actions that can be taken to prevent or at least delay this dismal scenario. Even if these efforts do not turn the tide, they will keep hopes and principles alive for future generations, and will provide our lives with meaning. His long list of crucial changes includes full employment; unionized work places; $15 an hour minimum wage; $500 a week to the unemployed, disabled, stay-at-home parents, the elderly and those unable to work; nationalization of public utilities; abolition of NAFTA; government funding for the arts and education; and a nuclear free world.

Citing Saul Alinsky and Marcus Gecan as sources of information on community organizing, Hedges says that progressive people will have to ally with those whose “professed political stances” are different from theirs (perhaps unemployed workers in the rust belt who voted for Trump.) Hedges admires the people of Standing Rock, North Dakota, who set up an encampment and halted the development of a pipeline on Sioux territory (through their drinking water supply and an ancient burial ground.) He mentions a Brooklyn group that organized to build 5,000 low income houses, and saved a neighbourhood.

Street violence is counterproductive, says Hedges. In Germany and Italy in the 1920s and early 1930s, street clashes between communists and fascists were frequent, giving the government the excuse for repression. In Norway and Sweden, which were also suffering economically at the time, the left used boycotts, demonstrations and low-bidding interventions in farm auctions occasioned by bank foreclosures . They went on to build societies with strong social safety nets.

America: the Farewell Tour is an impressive book. Readers who lack a background in economics but are troubled with what is going on in the world will be absorbed in his analysis. Hedges is no academic pronouncing from an ivory tower, but a reporter who has gone out among the victims of global capitalism to gather information. Some of the chapters appeared, in part, in Walrus magazine. His bibliography of over one hundred and fifty books shows the depth of his research. It includes a wide range of thinkers such as Barbara Tuchman, Rebecca Solnit, Niall Ferguson, Antonio Gramsci, James Baldwin, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Karl Marx, Adam Smith and John Locke, to name just a few. Apart from his rather tedious summary of a dystopian novel in the last chapter, the book is compelling, and the citations, quotes and summaries illuminating. America: the Farewell Tourshould inspire concerned people to think about what they can do in the “global fight for life against corporate tyranny.”

About the reviewer: Ruth Latta has a Master of Arts degree from Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario and has reviewed books for the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives magazine, The Monitor