Reviewed by Carl Delprat

Reviewed by Carl Delprat

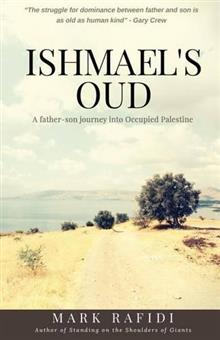

Ishmael’s Oud

By Mark Rafidi

Guillotine Press

2016, 216pp, 18 November 2016

Ishmael’s Oud is not a novel to speed through, so remove your dark glasses and make yourself comfortable; because we are off to visit many exotic places, including Jerusalem, Petra, Tel Aviv, Amman, the Jordan River, Nazareth, and even Stockholm, yes suddenly I find myself in Sweden with another of Ismael’s remembrances.

This isn’t just another Cooks Tour. The book takes the reader right through the divisions, the conflict and all the limitless troubles in this deadly garden of religious experiments. Mark Rafidi has tiled every page with a distinct selection of orientation and filled it with spicy metaphors. Sometimes he choses to focus on the father and son, and then flashbacks’, yes-unexpected flashbacks into Ishmael’s past collectively snap each jigsaw piece back in place. With every phrase, sentence and paragraph carefully trimmed and mitered an intriguing story emerges that flows into a family saga of blood and bone.

Ishmael’s Oud is a modern-day Odyssey where father and somewhat reluctant son re-open their individualities and experience a collective total actuality. It’s the narrative that draws me in because Mark Rafidi has chosen his wording so carefully:

Malik’s father has a rasp, a cough that hugs every word, shaped from a lifetime of cigarettes and hard work. He is bent when he walks, his face pointing to the grave he will soon occupy. (47)

Ishmael’s Oud contains another unexpected treat … poetry that unexpectedly emerges from between the pages, redirecting your mind and delivering vivid glimpses. Ishmael’s Oud made me imagine I could be a third wheel, this invisible pilgrim accompanying this father and son’s expedition. The story is beautifully worded, drawing the reader forward: “This could be any country in the world. Spin a globe, close your eyes and pick with your forefinger…”

Ismael’s Oud is a crossroads of culture, a religious melting pot, antiquity on tap, The Dead Sea, Beirut, eating pizza, eating knafeh, Palestinian border crossings, Jordanian borders crossings, and the authorities, the stringent monitoring and policing. It’s as if the land has been overwhelmed with reincarnated SS guards. It taught me what it is to be like a Palestinian, a refugee, a displaced and unwanted person in an ancient disputed piece of almost arid land fought over by practically the whole planet: that corridor used by every humanoid that departed northward out of Africa, sand, rock and dryness with nothing but history and violence as drawcards.

As for the Oud, one does get a mention in a Bedouin’s tent and a brief following description of the musician’s talents takes place. However, I found no connection with Ishmael Rafidi and an Oud anywhere in this story. I looked the instrument up on Google and U-Tube, the stringing reminded me of past harpsichords I had built. Yes there were seven harpsichords in total and two English spinets, however all of that was a long, long time ago and I have written a story based on this called The Harpsichord Man. I liked the sound, liked how the strings were doubled up and could be stretched, liked the shape of the bloated sound box, and its large soundboard with three sound holes. I could visualise its sound before I heard one play. So perhaps this Oud was only meant as a metaphor, a something special, a personal connection between father and son?Perhaps this book could also be named Ishmael’s Ossuary as this tale is filled with family skeletons and uncovered ancestors and far too many young men that once died far too early.

About the reviewer: Carl Delprat is a prolific storyteller. His home is the Australian coastal city of Newcastle, New South Wales. Find his books at: https://www.smashwords.com/profile/view/CarlDelprat