Reviewed by P.P.O. Kane

Reviewed by P.P.O. Kane

The Silver Age of DC Comics

by Paul Levitz

Art Direction and Design by Josh Baker

Taschen, 2013

ISBN: 9783836535762

This Brobdingnagian book measures about 24cm by 33cm across and has 400 or so pages, pretty much all in colour. At the very start there is an interview with the great Neal Adams, a comic book artist with a cinematic style who graced Batman with a sinister elegance (his Batman was modelled on Christopher Lee’s Dracula, if I remember aright), paving the way for Frank Miller’s later and even more radical reimagining of the Dark Knight. A short interview but one full of astute comments, and I was especially struck by Adams’ remark that Marvel’s creations (The Fantastic Four, Spiderman, The Hulk, etc.) ‘were essentially monsters turned into superheroes’. A surprising observation, but on reflection perfectly sound: Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, Marvel’s two main artists, were schooled in all genres, including horror comics. And significant too, since there has been a growing interest in monsters in recent years – and in what they might mean for we poor mortals – following on from Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s seminal Monster Culture. Indeed, one could characterise Adams’ Deadman – a pale, corpse-like revenant whose ontological status is uncertain – as a kind of monster.

The question driving Deadman, ‘Why was I killed?’, is not unlike ‘Why was I born?’, a question all reflective beings ask at some point. It also recalls the question the monster addressed to Frankenstein: ‘Why did you make me?’ Adams’ character is a dead man yet conscious, possessing desire and intention, so what else is he if not a hybrid, a freak? His tormented quest means that peace is a lifetime away.

The question driving Deadman, ‘Why was I killed?’, is not unlike ‘Why was I born?’, a question all reflective beings ask at some point. It also recalls the question the monster addressed to Frankenstein: ‘Why did you make me?’ Adams’ character is a dead man yet conscious, possessing desire and intention, so what else is he if not a hybrid, a freak? His tormented quest means that peace is a lifetime away.

The second section, ‘The Super Hero in the Space Age’, presents a history of DC Comics from the mid-1950s to the end of the ’60s. Though rather staid to start with (certainly when compared to EC Comics which came before and Marvel who came after), DC took more risks as the 1960s wore on. Paul Levitz attributes this change, in the main, to the appointment of artists, notably Carmine Infantino, famous for his work on Flash, to editorial and managerial positions. They certainly allowed the idiosyncratic Steve Ditko great freedom to develop his characters – The Creeper, The Question and Blue Beetle – when he moved over to DC and Charlton in the latter part of the ‘60s, after a fatal falling out with Stan Lee. In a way, The Question has always been rather an ironic title for a Ditko character for, like the philosopher Willard van Orman Quine, who removed the question mark character from his typewriter and replaced it with a mathematical symbol, Ditko had little tolerance for uncertainty or ambiguity.

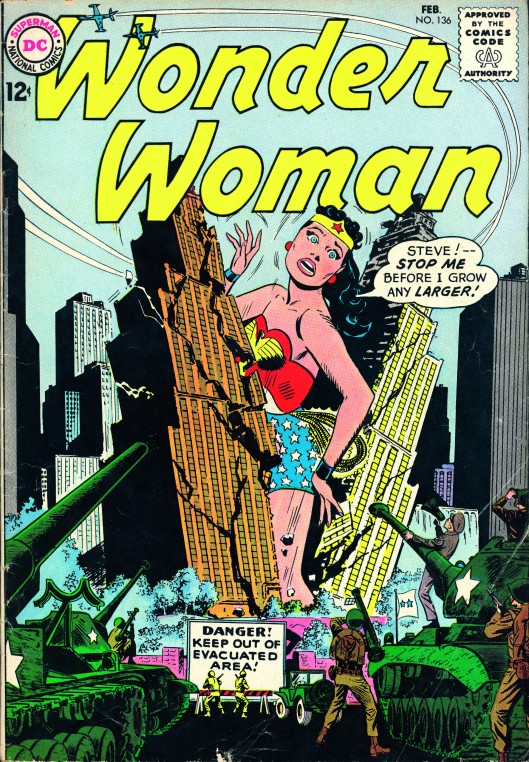

Now we come to the final section of the book, ‘The Silver Age, 1956-1970’, and it’s a feast for the eyes, well worth waiting for. It is best described as an opulent gallery of comic book art: some interior panels and pages but mainly covers. There was a widespread belief in the industry that children and teenagers (virtually the sole readership at that time) bought comics on the basis of the cover art, and that it was usually an impulse purchase. Hence the covers were often spectacular, or perhaps had a gorilla on the cover – since it was discovered that the latter sold especially well. Anyway, it is clear that one way to read a comic is to treat the cover art as a painting and the interior as a narrative interpretation of it. A strategy suggested by how they were put together. Here is a Batman cover from 1968:

Batman No. 205. Cover art, Irv Novick. September 1968. Copyright: TM & © DC Comics. All rights reserved. (s13)

Within this section there is a focus on the principal superheroes (Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, etc.) and their artists and writers, but other genres (war, romance, science fiction, espionage, westerns) are given their due too. Mort Weisinger, a scriptwriter on Superman, had what may well have been the most envious job in the world: ‘I often fantasised what I would do as the Man of Steel.’ He then wrote it down and incorporated it into a story. It happened. One might well ask whether Superman is a monster. For monsters are parasitic on human emotion; they embody our fantasies and dreams as well as our nightmares.

Some of the artists highlighted here are Neal Adams, Carmine Infantino and Steve Ditko, but there is also Gil Kane (Green Lantern), Curt Swan (Superman) and Joe Kubert (Sergeant Rock and other war comics: Kubert is the great comic book war artist): all comic book legends. What is particularly effective about the way this final section has been put together is that all the text – the exposition, judgement and opinion – is in the captions. A brilliant format: you can readily immerse yourself in the splendor and excitement of the art work, then return to read at leisure.

The Silver Age was the period when DC Comics deepened and developed its existing stable of superhero characters, as well of course as developing new ones. By doing this, they responded to the challenge posed by Marvel. Also, the DC Universe (or Multiverse) was made more complex and strange – the notion of parallel worlds was introduced, for example – if not as complex and strange as our own. This had crucial consequences much later; it led to Infinite Crisis and all that carry-on.

The Silver Age was the period when DC Comics deepened and developed its existing stable of superhero characters, as well of course as developing new ones. By doing this, they responded to the challenge posed by Marvel. Also, the DC Universe (or Multiverse) was made more complex and strange – the notion of parallel worlds was introduced, for example – if not as complex and strange as our own. This had crucial consequences much later; it led to Infinite Crisis and all that carry-on.

This sumptuous book is visually rich, informative and insightful, brimming with beauty. It is an ideal companion and guide to the Silver Age for novices and cognoscenti alike. (The latter might be heard to ask, ‘Why wasn’t I told about Jerry Grandenetti?’) While more than likely to ignite desire as well as satisfy it, the book can be warmly recommended to all comic book fans.

About the reviewer: P.P.O. Kane lives and works in Manchester, England. He welcomes responses to his reviews and you can reach him at ludic@europe.com