By Daniel Garrett

By Daniel Garrett

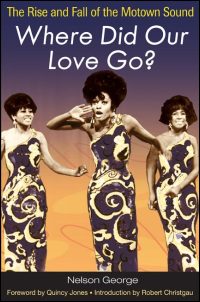

Where Did Our Love Go?

The Rise and Fall of the Motown Sound

By Nelson George

University of Illinois Press

2007, 250 pages, ISBN 978-0-252-07498-1

Considering Genius

Considering Genius

By Stanley Crouch

Basic Books/Civitas (Perseus)

2006, 359 pages, ISBN 13: 978-0-465-01517-7

“To live together in the world means essentially that a world of things is between those who have it in common, as a table is located between those who sit around it; the world, like every in-between, relates and separates men at the same time.” Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (Univ. of Chicago Press, 1958; page 52)

“What I bring to the table, what I’ve brought to all of the musical tables that has made this career lasting, is me. Just me. Naked of spirit with no other intention but to be of service to the music and to tell the truth.”—Chaka Khan, I Got Thunder (Thunder’s Mouth Press, 2007; page 72)

Birth, family, play, schooling, friendship, hope, insecurity, change, love, ambition, frustration, shared work, community, disappointment, accomplishment, separation, growth, illness, surprise, delight, bad habits, memory, new possibilities, resources, exhaustion, and death. Whatever life means to us, art and philosophy offer celebration, consolation, and illumination. Music, one of the most charming arts, can engage us with a new sound or an old feeling, holding us away from the mundane requirements of our lives, holding us in what seems a timeless moment.

2.

In the book Where Did Our Love Go? The Rise and Fall of the Motown Sound, originally published in the mid-1980s by St. Martin’s Press and republished in 2007 by the University of Illinois Press, the journalist Nelson George wrote, “What was Motown’s edge, the difference that made it work where so many others had failed? It was Berry Gordy, the talent he acquired, both on record and backstage, and the way in which he organized and motivated his personnel” (Univ. of Illinois Press edition, page 53). George, someone whose work I used to read in Manhattan’s Village Voice, documents the beautiful and brutal reality that was Motown, a company and a creative period, the 1960s through the 1970s, that I think of as a highlight of African-American and American history, as important as (if not more important than) the Harlem Renaissance, giving us sounds and substance, giving us ideas, images, and individuals, of great value.

3.

Tim Hughes, in his essay “Trapped within the Wheels,” published in the anthology Expression in Pop-Rock Music (edited by Walter Everett, Routledge, 2008), says about Stevie Wonder’s song “Living for the City,” an inventive and now classic song of protest: “Wonder fuses the collective with the individual, complexity with simplicity, and a controlled and rehearsed recording process with spontaneous flexibility. He also infuses modernist experimentation with deep cultural memory, and teaches the history of a tragic migration of millions through the story of a tragic journey by a nameless individual” (page 240). It seems to me that in that brief description—part of a larger, sophisticated exploration of Stevie Wonder’s work—is an appreciation for an African-American modernism in music that was accessible to all.

4.

“Motown’s sound was now surely the sound all young Americans loved. With the exception of the Beach Boys, no other American musical institution would so effectively challenge the Beatles’ monopoly of the pop charts,” wrote Nelson George of the dominance of Motown in the mid-1960s (Where Did Our Love Go?, page 103). Many of Motown’s artists—Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye, Diana Ross, and Smokey Robinson, as well as Gladys Knight and the Temptations and others—remain icons not only of that era but for modern popular music.

5.

I like the music of Africa and Asia, the music of Europe and the Middle East and Latin and South America; and I like blues, jazz, rock, and even some country and bluegrass—and my saying Yes, yes, and again yes to Motown is not just a personal or provincial declaration. I am not interested in mindless or merely reflexive affirmations: my concerns are aesthetic and intellectual. I think of myself as an individual, as cosmopolitan, as a citizen of the world, a fact that connotes a state of mind rather than a bank balance. I am also an American of African descent; and sometimes my response to “black” people has been one of affection and pride and at other times one of alienation and disappointment: and that is a result of seeing what is in front of me, intelligence or stupidity, truth or dishonesty, kindness or cruelty. (In fact, recently the point has been driven home that not only are many black people alive to sound, and alive in sound, but that many have a great tolerance for noise of all kinds; and as I get older, I do not.) I think it is difficult, if one is honest, to have a consistent response or relationship to whole populations; often such a response or relationship is no more than a fantasy, a lie, or a prejudice.

6.

There is a difference between fair and justifiably critical judgment and that of indifference or hostility; and, while rock and hip hop are seen as current and important, some forms of music do receive hostility; and some of the music that receives such hostility is identified with African-Americans, or women, or minority groups, such as jazz and ballad singing. Such music is not simply rejected because of those group associations but, sometimes, because of what those certain associations may be taken to mean—with jazz, an image of refined African-Americans may be part of what is rejected; and with ballad singing, and women, a certain depth of emotion may be what is rejected. Each year, there are a few musicians whose works are anticipated and celebrated by many critics, sometimes regardless of the quality of their works: that those musicians participate in privileged genres is enough. In recent months, in the last year or so, a lot of attention has been given to the album by Vampire Weekend featuring the songs “A-Punk” and “Cape Cod Kwassa Kwassa”; and also receiving attention have been Gnarls Barkley’s The Odd Couple, Erykah Badu’s New Amerykah, Iron and Wine’s The Shepherd’s Dog, Arcade Fire’s Neon Bible, and Bloc Party’s A Weekend in the City. While I like Gnarls Barkley and Bloc Party and what I have heard of Vampire Weekend and Erykah Badu, I have found more intriguing works that suggest maturity and tradition and its continuation and expansion: Jill Scott’s The Real Thing, and also Herbie Hancock’s River: the Joni Letters, Dee Dee Bridgewater’s Red Earth: A Malian Journey, Meshell Ndegeocello’s The World Has Made Me the Man of My Dreams, Kenny (Babyface) Edmonds’s Playlist, and Angie Stone’s The Art of Love and War. Those recordings by Jill Scott, Hancock, and the others I have named last are distinct, different, and it is their difference from one another and from what is often promoted as the sound of now that is fascinating to me. Someone such as Rahsaan Patterson, has given rhythm and blues something new, in terms of rhythms, vocal approach, and even lyrics. It made his album Wines and Spirits something that required several listenings for appreciation: it may be that, these days, the genre of rhythm and blues has a tougher time mediating tradition and invention than some other forms of music.

7.

Of course, what Herbie Hancock and Dee Dee Bridgewater are doing as musicians in an African-American improvisational music tradition, in jazz, bears some relation to the legacy of Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington and Miles Davis; and the work of an Angie Stone or a Rahsaan Patterson is a very distant cousin to that. The public intellectual Stanley Crouch, in his collection of music commentary Considering Genius (Basic Books/Civitas, 2006), defined the emblematic, life-sustaining work of Duke Ellington and the blues and jazz heritage he received, participated in, and transformed: “Yet it was the complex of sorrow and celebration, erotic ambition and romantic defeat—always fueling the deepest meanings of the blues—that sensibility also inspired him to the sustained development of his composing techniques, for it could be brought to any tempo. The timbres discovered in blues singing and blues playing could color any kind of piece, keeping it in touch with the street, with the heated boudoir beast of two backs, the sticky red leavings of violence, the pomp and rhythmic pride of the dance floor, and the plaintive lyricism made spiritual by emotion that has no specific point of reference other than its audible humanity” (138).

8.

I do not know that I can describe in any rigid way the work of the singer-songwriter Nona Hendryx, who performed with the group Labelle and released her own innovative music albums: the singer-songwriter Nona Hendryx was interviewed by LaShonda Katrice Barnett for the book I Got Thunder (Thunder’s Mouth Press, 2007), which features interviews with musicians such as Hendryx, Abbey Lincoln, Angelique Kidjo, Chaka Khan, Dionne Warwick, and Joan Armatrading; and Hendryx describes herself as being open to receiving music, declaring, “I believe I was meant to listen and hear the music. I’m a transcriber, basically, of musical information. And I had really no other choice but to do this, because this is what was given to me when I was created. So to say to someone who has a desire to do this—and I speak to many aspiring artists—the work you do in a sense is not a chosen work but a vocation. You come to it because you’re prepared for it in some way. When I say I make myself available to what is in the air, I mean that is my sensitivity; I’m a sensitive observer” (page 164). That receptivity, a willingness to hear and to see and to learn, is shared by other artists and by some critics.

9.

Years ago, Susan Sontag in her essay “Against Interpretation” (published in a book of the same name in 1966 by Farrar, Straus; and reissued by Anchor Books/Doubleday in 1990), discussed matters of cultural reception, including the inclination of intellect to be pursued at the expense of emotion, energy, and sensuality, and the inclination to see criticism, primarily, as interpretation (an interpretation that can replace art itself), and her preference for a descriptive criticism that paid attention to form, a preference that led her to affirm transparency, “experiencing the luminousness of the thing in itself,” ending in a call for an erotics of art (Anchor edition, pages 7 to 14).

10.

Whether in criticism of art (fine, folk, or popular) or literature, the identification of the intricacies of form and the nature and exultation of spirit in a given work, with an appreciation of the pleasure the work offers, remains a daunting and significant task, one not always met when discussing a painting or film, a story or poem, rock or jazz: “Like most American criticism, jazz writing is either too academic to communicate with any people other than professionals, or it is so inept in its enthusiasm or so cowardly in its willingness to submit to fashion that it has failed to gain jazz the respect among intelligent people necessary for its support as more than a popular art,” wrote music and social critic Stanley Crouch in his collection of essays and reviews Considering Genius (Basic Books/Civitas, 2006, page 221). (Crouch has stated also that he has no particular interest in “black recording labels such as Motown that showed no affinity for jazz,” on page 226 of Considering Genius—an irony, in light of Motown president Berry Gordy’s early interest in jazz.) In criticism of art, literature, or music, it is easier to talk about whether something is conventional or popular rather than whether it is good.

11.

In Considering Genius, Stanley Crouch writes about Miles Davis, Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, Ahmad Jamal, Charles Mingus, Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane, and many other very gifted musicians; and he writes about the concerns regarding aesthetics, business, society, and politics that affected the musicians, their music, and how their music is interpreted. It is a similar service that Nelson George performs in writing about Motown, and the musicians of Motown, those who are well known and those who remain obscure, and the business people of Motown, and their aspirations and gifts and conflicts and disappointments and accomplishments, which have made the company legendary.

12.

The people who write about music sometimes champion the work of those whose ideas and images closely mirror their own, in terms of class, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality, but some writers are more imaginative, more intelligent, seeking out the widest possible range of music and musicians. Some of the commentators on music whose insights have enlightened and/or entertained me are James Baldwin, Playthell Benjamin, Delphine Blue, Nate Chinen, Kandia Crazy Horse, Stanley Crouch, Angela Davis, Jim DeRogatis, W.E.B. DuBois, Ralph Ellison, Christopher John Farley, Nelson George, Farah Jasmine Griffin, Claudrena Harold, Pauline Kael, Greg Kot, Will Layman, Wynton Marsalis, Michelangelo Matos, Paul Nelson, Sarah Rodman, Kelefa Sanneh, Gene Seymour, Armond White, and Carl Wilson. I always recall Baldwin’s comments on Bessie Smith and Billie Holiday, and Pauline Kael on Streisand and the Rolling Stones. One of the more interesting music writers now is Christian John Wikane. I encountered his work on the pages of the web magazine Pop Matters, which publishes great commentary on books, film, music, and other disciplines and issues. (My own commentary on Annie Lennox and the band The Smyrk appeared there.) In his writing, Christian John Wikane has featured the work and personalities of Ashford and Simpson, Gnarls Barkley, the Bee Gees, Tim Buckley, Don Byron, Paula Cole, Donnie, Feist, Aretha Franklin, Kevin (Ké) Grivois, Deborah Harry, Jamiroquai, Chaka Khan, K.D. Lang, Bettye LaVette, Amos Lee, Annie Lennox, Paul McCartney, Mika, Madonna, Stevie Nicks, Rahsaan Patterson, the Pointer Sisters, Corinne Bailey Rae, Nile Rodgers, Linda Ronstadt, and Diana Ross. Wikane called Gnarls Barkley’s The Odd Couple “an emotionally and musically provocative album,” a recording that is an “alternately disturbing, comforting, and challenging exploration of the human mind” (PopMatters.com, March 25, 2008); and Wikane remarked of K.D. Lang’s first album of new songs in years, Watershed, that Lang demonstrates “a keen sense of how to record herself and lead her excellent unit of musicians” (PopMatters.com, Feb. 5, 2008), and he enthusiastically declared of the anthology Bee Gees Greatest that the word “‘greatest’ seems far too modest an adjective to describe this music” (PopMatters.com, October 8, 2007). Christian John Wikane’s love and respect for music and its makers are refreshing; and his commentaries—reviews of recordings and interviews with artists—are among the most complete responses to music available. His work is quite intelligent, but in light of his attention to emotion and sensuality in music, and the empathy and enjoyment he brings to encounters with musicians, I have thought that his work contains the beginnings of an erotics of art.

13.

I have loved Joni Mitchell’s work since I was a boy, and while I no longer listen to her almost every day, as I did when I was in much of my twenties, she remains high in my regard. She has had and does have some diverse and demanding admirers—among them, Tori Amos, Bjork, Bob Dylan, Herbie Hancock, Emmylou Harris, Janet Jackson, Chaka Khan, Charles Mingus, and Prince. Christian Wikane reviewed the Joni Mitchell tribute album produced by Nonesuch in April 2007, a recording that featured Bjork and Emmylou Harris and Prince. Joni Mitchell has complained for years about the aesthetic and age prejudices attendant to popular music. Much of popular music, and of popular culture, is seen as the province of the young, to which adult consciousness and concerns must be marginalized or prohibited.

14.

People interested in music can learn about and even hear new music via the internet, and also television, radio, magazines, newspapers, and through the comments and courtesies of friends; and new sources for music, such as the internet, have been seen as threatening by the music industry, the network of businesses that record, package, and distribute music. In Christian Wikane’s June 25, 2007 PopMatters.com piece on Paul McCartney, McCartney says about record companies, “I think that they admit themselves that they’re in a very awkward time. They had it all their own way for a number of years. They’ve got huge stables of acts and artists on their books so it’s very difficult to get singled out as an artist. You can’t get arrested. You’ve got a good album and no one will listen to it just because they’ve got to listen to 300 other albums. I think that’s the phenomenon that people are getting fed up with.”

15.

Ké, that is Kevin Grivois: I had heard his album I Am [ ] at the time of its release, in the mid-1990s, and I had thought it one of the most intense, unique recordings then available and my tastes then were all over the place—Afghan Whigs, Aster Aweke, David Bowie, Mariah Carey, Dionne Farris, Fugazi, PJ Harvey, Hole, John Lee Hooker, Shirley Horn, Miki Howard, Howlin’ Wolf, Abdullah Ibrahim, Chris Isaak, Michael Jackson, Lil Louis, Lisa Loeb, Alanis Morissette, David Murray, Tony Rich, Skunk Anansie, Smashing Pumpkins, Matthew Sweet, A Tribe Called Quest, and Cassandra Wilson. I would sometimes listen to Ké’s album I Am [ ] very early in the morning, when preparing for my day; and as the years passed I would think about the singer-songwriter and what he might be doing, whether he had recorded anything else. He had a great deal of difficulty with his record company, which wanted him to simplify his presentation of both his identity and his work, and failed to properly promote his work. His spirit remains strong but his story is a cautionary tale.

16.

Artistic independence, like personal independence is sometimes valued, sometimes not, as with Kevin Grivois, as with Marvin Gaye: “As warm and charming as Marvin could be, especially to the women who sighed at his long eyelashes, smooth skin, and sly, ingratiating smile, there was an impetuous, evil side to him that could flare easily. ‘I’m an individual and I demand that I be treated as an individual and not as cattle,’ he’d say, adding, ‘My position and my independence has gotten me into a great deal of trouble in the past, but I’ve managed to overcome it because my convictions are honest.’ To Marvin it may have been a matter of integrity, but to even his friends, like Pete Moore of the Miracles, he could come off as ‘unusual, bizarre, erratic’” (Nelson George, Where Did Our Love Go?, page 132).

17.

Print publications have felt challenged by the internet, where there is much original and vibrant cultural commentary; and some of those publications have let reviewers—music, film, and other critics—go because of that challenge, eliminating or narrowing an avenue of intelligent discourse (that is, when the people they are firing aren’t dull and antagonist to complex or new aspects of music, film, literature and other culture). Yet many publications are leery of hiring writers who have had a significant association with the internet.

18.

I had a revelation recently: mediocre people are led by fear and exceptional people are led by hope (and that exceptional people betray themselves, act outside their nature or gift, when they allow themselves to be shaped by fear). I think fear leads to thoughts and behaviors that are self-denying and self-destructive, even if those behaviors are called acts of duty or responsibility, or a pragmatic concern for social security (and social security checks); and that hope leads to ideas and acts that are self-enlarging, self-expressive, and self-preserving, even when such commitments can make one seem adrift, and irresponsible, to others. I came to these conclusions after someone told me that wanting to be an artist and intellectual after a certain age, if one had not found worldly success, was nothing more than a youthful dream that had lasted too long.

19.

There is a great deal of pleasure involved with the arts, and some glamour, but many people do not understand the actual work that is involved in the lives of artists, writers, or critics: the education in cultural traditions, the mastery of materials, the trial and error of experimental work, the social and professional negotiations and vulnerabilities, the solitude, the constant attention—and the rewriting.

20.

There are different kinds of sabotage an artist or thinker encounters, some malicious, some well-intentioned. I have had some experience with questionable editing. Once I did a piece on a Spike Lee film about male relationships, Get on the Bus, and I discussed the epic of Gilgamesh, about two warriors, and I referred to the first presidential campaign of Bill Clinton and Al Gore, and the editors eliminated the Clinton/Gore segment. In a review of Gavin Dillard’s poetry, I referred to the “construction of sexuality” and an editor changed that to the “constriction of sexuality,” not the same thing at all; and more recently in a review of Richard Burgin stories I affirmed that Burgin had done “work” that Chekhov would like and an editor changed that to “a work” that Chekhov would like. Some people do not realize that small changes affect the meaning of a statement; and changed meaning alters the understanding a writer wants to impart.

21.

The philosopher Hannah Arendt, in the book The Human Condition (“The Public and the Private Realm”), spoke about wisdom and goodness in a way that gives me pause: she wrote, “Love of wisdom and love of goodness, if they resolve themselves into the activities of philosophizing and doing good works, have in common that they come to an immediate end, cancel themselves, so to speak, whenever it is assumed that man can be wise or be good. Attempts to bring into being that which can never survive the fleeting moment of the deed itself have never been lacking and have always led into absurdity” (Univ. of Chicago Press, 1958; page 75). Hannah Arendt is saying that we can perform occasional acts that are wise or good but we ourselves cannot be so always; and that reminds me that when I was younger I thought I would become ever more perfect manifestations of my self, an inspiring belief that became frustrated, then tragic, and now—despite whatever pride I take in aspects of my character, mind, and work—the belief seems quite hilarious. Yet, one laughs or cries and struggles on—thinks, works; and hopes.

22.

I have thought a lot about the campaign of Senator Barack Hussein Obama for president. He seems to embody American possibility; and American reality—the cultural exchanges and the political progress that writers such as Ralph Ellison and James Baldwin wrote about years ago; and the ambiguity and personal initiative that performers such as Ethel Waters and Paul Robeson, Sidney Poitier and Diana Ross, Muhammad Ali and Oprah Winfrey were the living emblems of for years. (Some of us are not the children of Karl Marx and Coca-Cola, but rather the children of Martin and Motown, of King’s civil rights marches and the music of the ambitious young performers and producers of Motown.) I can imagine a cultural festival inspired by Barack Obama that would include the established Motown performers (Stevie, Diana) and also performers such as the band Vampire Weekend (preppies playing Afropop music) and the singer Sade and others who signify an integrated culture.

23.

“I have asserted a firm conviction—a conviction rooted in my faith in God and my faith in the American people—that working together we can move beyond some of our racial wounds, and that in fact we have no choice if we are to continue on the path of a more perfect union,” said Barack Obama in Philadelphia, March 18, 2008.

24.

What we choose to do, and what we do, determines to a great extent the character and tone of our lives, its pleasures and pains, its successes and failures; and each life is bound to, and is influenced by and influences, other lives. Hannah Arendt, in The Human Condition (“Action”), wrote: “Although everybody started his life by inserting himself into the human world through action and speech, nobody is the author or producer of his own life story. In other words, the stories, the results of action and speech, reveal an agent, but this agent is not an author or producer. Somebody began it and is its subject in the twofold sense of the word, namely, its actor and sufferer, but nobody is its author” (Univ. of Chicago Press, 1958; page 184).

25.

Books such as Native American Music in Eastern North America by Beverly Diamond (Oxford University Press, 2008) and Iroquois Music and Dance by Gertrude Kurath (Dover Publications, 2000) help us to learn more about the earliest Americans, the indigenous people who made so much of our common inheritance possible.

About the reviewer: Daniel Garrett is a writer of journalism, fiction, poetry, and drama. His work has appeared in The African, AIM/America’s Intercultural Magazine, AllAboutJazz.com, AltRap.com, American Book Review, Art & Antiques, The Audubon Activist, Black American Literature Forum, Cinetext.Philo, The Compulsive Reader, Film International, Frictionmagazine.com, The Humanist, Hyphen, Illuminations, Muse-Apprentice-Guild.com, Offscreen.com, Option, PopMatters.com, The Quarterly Black Review of Books, Red River Review, The Review of Contemporary Fiction, The St. Mark’s Poetry Project Newsletter, 24FramesPerSecond.com, UnlikelyStories.org, WaxPoetics.com, and World Literature Today. His extensive “Notes” on culture and politics appeared on IdentityTheory.com. Daniel Garrett’s internet interviews with music scholar Walter Everett, jazz critic Greg Thomas, and musician Felice Rosser of the band Faith, have been featured on the web pages of The Compulsive Reader, along with Garrett’s music reviews of jazz, blues, rock, pop, and world music. Author contact: dgarrett31@hotmail.com