|

Reviewed by Magdalena Ball Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

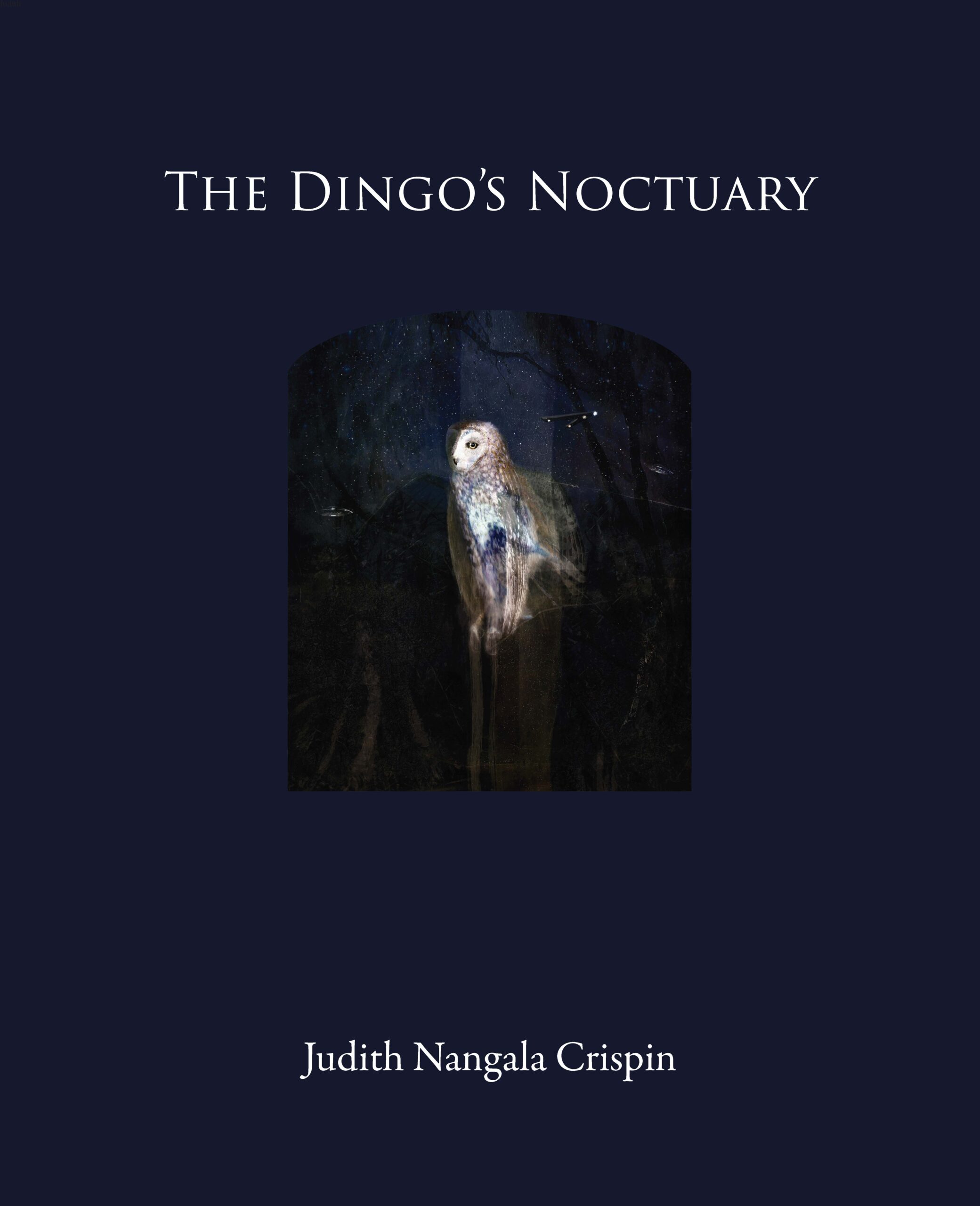

The Dingo’s Noctuary

by Judith Nangala Crispin

Puncher & Wattmann

November 2025, ISBN: 9781923099715, $130au, Hardcover

Judith Nangala Crispin’s new book, The Dingo’s Noctuary, is utterly beautiful, both in terms of its content and as artefact. The book is a solidly bound hardcover with 88 colour plates including a number of Nangala Crispin’s striking lumachrome glass prints. These prints use a unique process that Nangala Crispin created herself, placing animal and bird roadkill on emulsion and developing their shapes in sunlight via the chemicals emitted by the creature in combination with the paper. The end result, a camera-less photo, is haunting, almost lit from within, revealing something essential about the creature and maybe about all of us. The description of each picture is a poem in itself, naming the creature and giving it a second, spiritual life in the cosmos, for example:

Ascending Being 15—Ruth remembered the lit highway, then dark. And in that darkness she was singing, throwing out song like a rope, then flowing it up, earth pulling away – a song connecting bird and star and land. Everything splits, in the end, becomes tangled in stars.

The Dingo’s Noctuary is classed as an illustrated verse novel, and it does follow a fairly straightforward narrative of a journey taken by the author on Suzuki DR650 motorcycle with a dog called Moon through the remote Tanami Desert in northern Australia. The story moves in a linear fashion from the 22nd of September 2016 to the 17th of September 2017, arcing through the desert, but The Dingo’s Noctuary is no ordinary novel. It’s a hybrid creation, as the title indicates, a record of things passing by night. The book resists categorisation, impacting the reader on multiple levels, using different modalities including images, visions, dreams, poems, diary “noctuary” entries, artwork, pressed flowers, and terrestrial and stellar maps. In addition to the main narrative, there are multiple other stories that happen in parallel. One of those follows the trajectory of NASA’s Cassini–Huygens, a robotic spacecraft sent to study Saturn and its rings and moons, on its final impact course from April 2017 through to Sept 2017 when it burned up after plunging into Saturns atmosphere. The story of Cassini forms an alternative narrative, and one that is cleverly tracked against the desert story, paralleled in the astronomical imagery of the work, both text and image:

The day my uncle died, I dreamed he was suspended between Earth and the satellites in a

silken cocoon. There are spider-strings like electric wires, connecting us to everyone we’ve

ever loved—mother, grandmother, mothership.

The day my uncle died, Cassini turned above an extraterrestrial ocean to watch a moon

being born.

Have you ever wondered what it could mean to be free from all this culture? These stories

of belonging? All these beautiful names?

Through a break in Saturn’s clouds, Cassini sees a gargantuan hexagonal storm rage

around the pole—electricity and convective gyres. Ammonia and ice mist plume into the

atmosphere on powerful winds. Cassini, silvered in nocturnes of shifting stellar rays, listens

above the storm to Saturn’s lightning. (“First Noctuary Entry”, “Cassini”)

There are so many interconnecting threads–linguistically, semantically, rhythmically–connecting heaven and earth, ancestors and descendents, past and present, human and earth, individual and collective beings. The writing is consistently lovely throughout but also intense, exploring notions of identity, creativity, loss, colonisation and deception, the body and its relationship to country, and the conflicting nature of the self. The characters that people this book have their own stories: Lily the visionary painter, Astrid who is accused of a theft she didn’t commit, young Alfy who took his own life, Henry the UFO watcher whose one wish is to die in Purrkiji, his sacred Country, and Charlotte Clark, Nangala Crispin’s aboriginal great grandmother whose identity was purposefully hidden. The characters are found, lost, and transform into new forms, but their presence remains strong, in ghostly remnants and the ver present spider webs of connection:

It reminds me that, inevitably, we will lose everyone we love, to accident, violence or old

age. Cancer will take the rest. We’ll outlive every dog who’s ever loved us, except perhaps the last.

And every loss will leave us rudderless, in a sea of photographs and emails—social media

pages that will never be updated again.

Loss catches us mid-sentence, like when the phone signal drops—and we realise we’re still

talking, but the connection’s broken, and no one’s listening on the other end of the line. (“Twenty-third Noctuary Entry”, “Space Ants”)

There is magic on every page. This is not separate from the concrete description, but inherent in the scenery and settings of the desert seen from the motorcycle revealing the geological time of dry river channels, ridges, quartz fragments and tributaries. Often the trip is dangerous, a word that repeats throughout the collection. Nights are always dangerous, the clouds are pierced by dangerous stars, places that are too dangerous to reach by motorcycle, the heat makes it too dangerous to ride, the country has become dangerously unhinged, embodiment is dangerous. Manta Rays, shells, Comets, hope in the desert, and silence:

I can’t tell you what a soul is, but I know it’s dangerous at night,

under stranger planets, when wind shifts

its auguries of cloud across the moon. And like you,

I know the world is ending—I saw the future in a taipan

crossing, streamlined and purposeful, into my campfire’s circle,

starlight sliding over her scales. (“Eighth Vision”, “There is also a body of stars”)

The other kind of danger is evil, colonisation, destruction, forgetting the way the human is intertwined with nature. This is typified by Delamere Air Weapons Range and Bradshaw Field Training Area – the Australian home of the US military, wrapping evil tentacles around the land:

They drop explosives, pyrotechnics, satellite guided weapons that make the sky burn. These painted caves, these ghost gums loved by Namatjira, just collateral in the global offensive of oil, guns and Christ.” (“Fourth Noctuary Entry”, “ii: The Shadowless lights”)

Then there is the evil represented by organised religion at its worst, as typified by Billy Graham and other evangelists and missionaries. Evil is the killing instinct that won’t be sated. It’s a story of slaughter and extinction:

Evil germinates its seeds in ordinary gardens. By the time you’ve noticed, its taproot is deep, and all your other plants are dead. (“Fourteenth Noctuary Entry”, “Woman’s hunt at Mirirrinyunga”)

One of the most tender story in the book is the story of Moon, the goggle-wearing, pragmatic, Warlpiri jarntu/warnapari dingo-dog, who rides pillion on the motorcycle. At one point Moon nearly dies by snakebite, a piece of writing that brought me to tears, conjuring one the many types of intelligences in this book – that of a sentient non-human creature. The unconditional love here is so powerful it’s almost subversive:

There’s a calm that comes when everything is finished. I pull myself together and for the next six hours, just talk to him—investing stories of miraculous dogs with bodies of lightning and serpents and rain. I tell him what he means to me. I tell him he’s a good dog—winding my voice out like a rope to hold him, to stop him. Unravelling into that whirring spinning night. (“Twenty-first Noctuary Entry”, “Voyage to Katherine via Andromeda”)

The Dingo’s Noctuary is also the story of language and the many routes to expression, not just in human semantics but through patterns like constellations, history echoing through country, sign language and names, carvings and pictures etched in stone, and the language of flora and fauna, wing sounds and whistling kites – a different way of listening and speaking that can be illusive to human ears. Learning this language, or even acknowledging these other ways of speaking, is crucial:

The desert needs no breath to speak. It communicates narratives of rain and waking leaves,

mushrooms, bark and root.

Everything that lives has a language. And maybe those languages are more than uttered

signals, more than mechanisms to transmit ideas about the world.

Maybe language creates worlds.

The Dingo’s Noctuary doesn’t soften the message. We are most probably doomed, we won’t be forgiven, and danger and evil have wrapped around everything. All this notwithstanding, there is still something miraculous that happens in The Dingo’s Noctuary. The idea that we are all en route to returning to outer space is a healing and consoling thought, bringing together the many themes in the book in a way that is both beautiful and heartbreaking. At $130,The Dingo’s Noctuary is not a cheap book, but it is a work of art, and one that continues to call the reader back to find new threads, new stories, and new transformations. This would make a stunning and perfect gift for someone you care about, and the fact that all author profits are going to support training programs and a remote dialysis unit in Lajamanu by The Purple House, makes it even more wonderful. The Dingo’s Noctuary is an incredible book and one which merits extensive readership. It has something important to convey. Something painful, exquisite, and true. It expands the heart with its luminous imagery and prose.

|